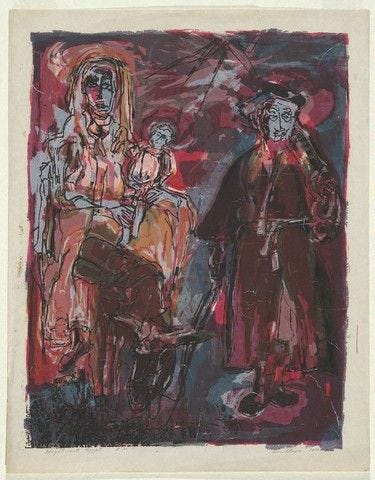

A Christmas Version 2025: The Flight into Egypt (and Luke's Nativity, and John's Prologue)

Luke 2 (link provided); John 1 (link provided); Matt 2:13-18 (19-23)

On Christmas Eve or early Christmas Day, most of us will hear Luke’s nativity story, which I commented on here in 2024 (note some redundant references to the Year C setting). Some will hear on Christmas morning—and in The Episcopal Church only, on the Sunday after Christmas—the Prologue of John’s Gospel, commented on in 2023 here.

If on Sunday 28th you are keeping either the Sunday after Christmas (other than for TEC) or Holy Innocents, the Gospel is Matthew 2:13-18, or 13-23. With the story of the Magi reserved by tradition for the Feast of the Epiphany, this has us jump from the bare mention of Jesus’ birth (1:25) to a second angelic dream for Joseph, warning of Herod’s murderous plans. While there is some discontinuity resulting in the narrative, the pattern of dreams, angelic guidance and scriptural citation reminds us that this is still the same story we were reading last week.

Joseph again dreams of an angel, who this time warns of danger and instructs the family to flee to Egypt. The reason for the danger has not yet been fully revealed, although in the passage left aside for Epiphany we get a sense of the build-up of Herod’s scheming, resulting from the report of the Magi about a new king (2:2). The angel now gives a brief indication of what is to come because of Herod’s murderous intentions; and so the family departs as refugees.

Although Egypt like Judea was under Roman dominance, there was no universal government or law; Rome was a military occupier and extractor of taxes and other forms of plunder, but did not supplant local laws or even all forms of government. Hence, to this point at least, Herod really was a king even if he ruled at Augustus’ pleasure. Attempts in the present day, driven by current political currents, to downplay the family as seeking asylum do not work any better historically than they do morally.

The reason for flight being obvious, Egypt was not necessarily self-evident as the destination, although its proximity makes it plausible. Egypt was almost a traditional place to flee (see, e.g., Jer 26:21). Matthew however wants the reader to understand the significance of the particular choice, with a quote from Hosea (11:1) to help us along. The reference in the original is to the Exodus, and God’s call to Israel itself, which collectively is also called God’s son. “Israel” was originally another personal name for Jacob the patriarch, and so this use of the collective and the individual to refer to each other is part of Hosea’s text too. Now for Matthew Jesus represents Israel’s past and future experience in his own.

Nothing else is said about this Egyptian sojourn, or even how long it was; Matthew does not date either Jesus’ birth or Herod’s death other than by this episode, which implies they were not very far apart in time. It is not really odd (pace Harrington, Luz, and others) that this citation referring to a call “out of Egypt” is provided just when Jesus is going in the opposite direction; this is clearly scene-setting. Matthew’s concern here is to explain how, when this drama was past, Jesus could also be called from Egypt, and to show that he himself embodies Israel. His arrival as God’s son is also aligned with the liberation of Israel, with God’s characteristic action and presence shown in saving his people again.

Herod’s rage then brings on one of the most terrible stories in the Bible, a “massacre of the innocents” as it is known. Tradition makes them the “Holy Innocents,” a remarkable kind of saint who never knew Jesus, but who were his companions (see below) and proxies in death. Herod was certainly a “massacrer of innocents,” although no other evidence exists for this particular atrocity. Josephus the historian, writing later in the first century and hence a contemporary of Matthew, provides plentiful examples that at least confirm this episode is in character.

Matthew’s intention here however is not to chronicle this king’s particular misdeeds so much as to relate them to the story of Jesus. When he had been with the Magi before this, Herod’s identity as “the king” (2:1,3) had been juxtaposed with Jesus’ being called by the sages “the king of the Jews” (2:2)—a title that will return to Jesus only at his trial and execution (27:11, 29, 37). This implies that Herod is illegitimate, or at least that his days were numbered. The appearance of the title for Jesus only at the beginning and the end of the story also suggest the deliverance of Jesus and his family is temporary; he will die, if not in time with these companions then in solidarity with them nevertheless, and because of this claim. All this foreshadows the kind of reign he will proclaim and embody.

The parallel with the story of Moses is not subtle: “the decree of death from the wicked king, flight to escape the decree, the slaughter of innocent children, and the return after the death of the wicked king.”1 The Egyptian connection also makes its contribution to this parallel, if only indirectly; Herod is now a sort of Pharaoh, and Judea is now the place of tyranny. As well as being a new Jacob/Israel, Jesus will liberate his people through a new Exodus.

Matthew continues the characteristic citation of scripture to interpret these last events too, now quoting Jeremiah (31:15). Just as Jesus was earlier depicted as Israel, alluding both to the people as a whole but also to the patriarch Jacob who bore that name, now Rachel, Jacob/Israel’s wife, weeps for her children, again the ancestor representing the nation. This is not divine action however, but illustrates the cruelty and illegitimacy of Herod who was “King of the Jews” but murderer of his people.

If we imagine knowledge of the passage on Matthew’s readers’ part, its interpretation is affected by the fact Jeremiah was not referring to murder but to exile, and that the passage was actually one of hope. The prophet immediately goes on:

Thus says the Lord: Keep your voice from weeping, and your eyes from tears;

for there is a reward for your work, says the Lord:

they shall come back from the land of the enemy;

there is hope for your future, says the Lord:

your children shall come back to their own country (31:16-17)

This of course would be in keeping with the holy family’s flight and return too. The story as a whole then depicts the plight of Israel at the time of Jesus’ birth and sets the scene for his ministry. He is God’s son, not merely because of the curious birth but because he has cast in his lot with the marginal and the displaced. Into a land where invaders and puppets rule this true king comes, not to replace them with a better version of despotism, but to share the plight of his people.

Further reading:

Aspray, Barnabas. “Jesus Was a Refugee: Unpacking the Theological Implications.” Modern Theology 40, no. 2 (2024): 386–403

Davies, John A. “Matthew’s Infancy Narrative and Jeremiah 31.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2025): 465–81.

Thanks to Misty Krasawski for research.

Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, p. 45

Of course, if you are "lucky" enough to have St. John as your patron, you get to do a mashup of Christmas 1 and the Beloved Disciple. It actually works pretty well.