Attentive readers will have noticed that last week it sounded very much as though the whole Gospel of John had reached a conclusion after the appearance to Thomas (20:31). Scholars agree that this must have been the end of an original version or draft, although no complete manuscript without ch. 21 exists. Yet here we are, with further material concerning an appearance in Galilee, and some reflections on the future role of Peter (and of the beloved disciple, although this is not read). It seems likely that even before its publication, what we know as John’s Gospel was expanded, whether by the same author or (more probably) by another editor with a relationship with the same setting or community. How to understand this appendix or epilogue?

There are other indications that this last chapter is different, some of them evident in the story of the miraculous draft of fish. John had not otherwise characterized the disciples as fishermen, although it was presumably common knowledge about a few of them. Now however a group who sound intriguingly like a mix of synoptic and Johannine characters—“Simon Peter, Thomas called the Twin, Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, the sons of Zebedee, and two others”— have for some reason returned to (or taken up) fishing. The presence in the list of Nathanael, who only appears in John (1:43-51), shows this compiler shares a tradition with the rest of the Gospel; even more so we learn a bit later (v.7) that one of them is the “disciple whom Jesus loved,” usually identified as the principal author of the Gospel, by tradition John.

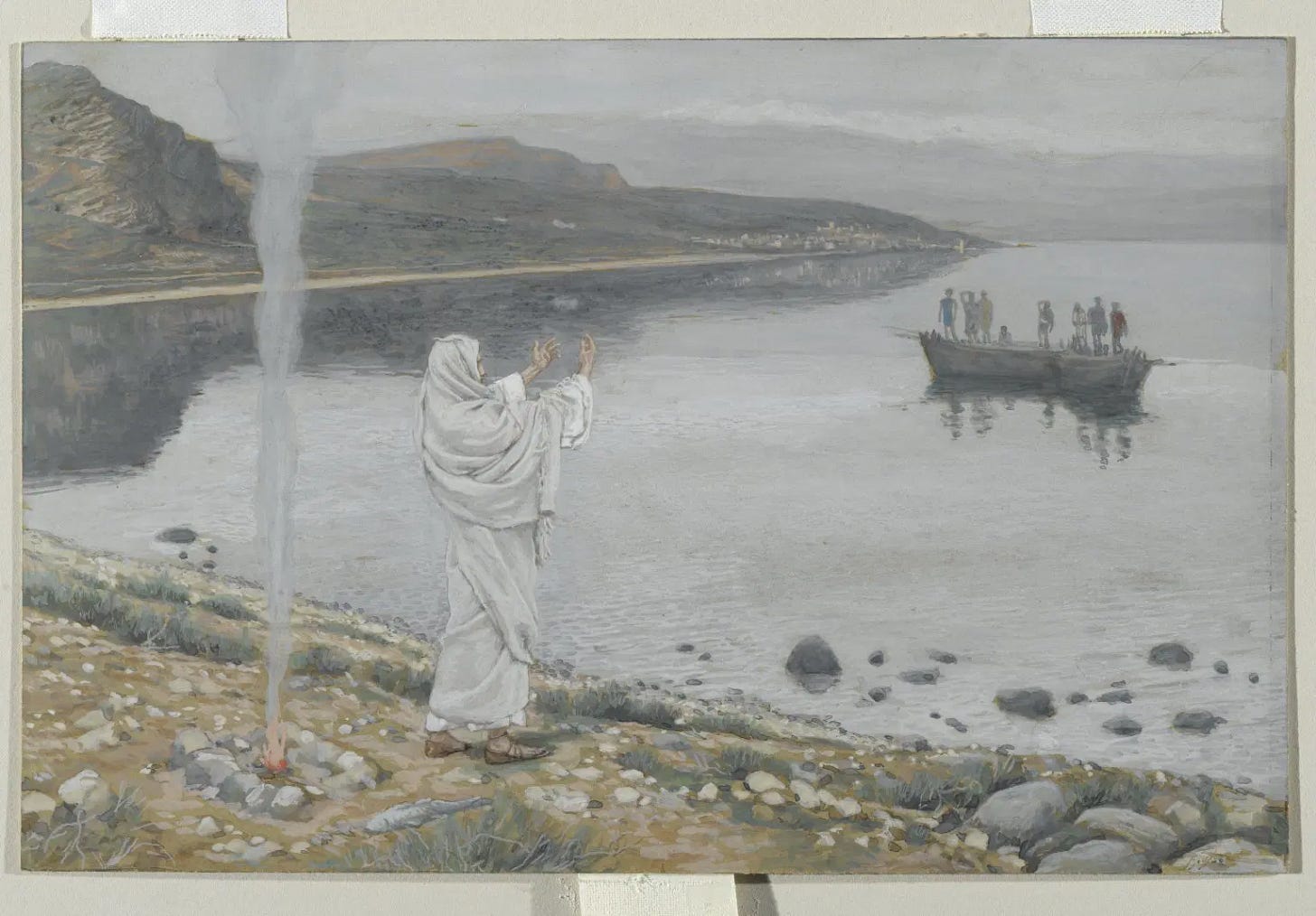

The motif of not recognizing the Easter Jesus, while familiar across Gospel tradition, sits awkwardly here after the stories of his revelation and commission of the same disciples in the previous chapter. It adds to the sense that this story has come from elsewhere, part of the memory of Galilean appearances not included in the earlier draft, and ultimately deemed important to include despite the rough narrative edges it causes.

This miraculous haul is itself both like and unlike the rest of John. The abundance of fish resonates with the symbolism of wine at the wedding at Cana story (ch. 2), and the sign of the loaves (ch. 6). So it can be understood as a further sign of the abundance of the reign of God (or as John might prefer, eternal life). Like those cases, there is a specific measurement involved too. While the other numbers (six jars, each with two or three amphoras’ volume at Cana, and five loaves with two fish in the wilderness) have sometimes made readers wonder about some additional meaning, the 153 fish of this story is weirdly specific.

There have been many inconclusive attempts to decipher this figure. Some have tried to work with mathematical symbolism and others with gematria (the interpretation of numbers as letters). Augustine points out that 153 is the sum of all the numbers from one to seventeen, or (to put it visually) the number of points in a triangular figure or pyramid made up of seventeen points on each side. Ten and seven (=17) are both numbers with biblical significance (there are seven disciples on this expedition too), and so on.

Interesting as this may be, it cannot be solved. And while in the rest of John’s Gospel the signs that Jesus performs are mysterious to their audiences in the narrative, they are expanded into opportunities to teach his identity, and quite clear to the attentive reader. Here though we have less a sign than a conundrum, something that either relies on information we no longer have or is meant to wrack our brains. Another, not mutually exclusive, possibility is that this number is just a detail that adds to the sense of historical verisimilitude, something we do find elsewhere as a concern in John.

The size of the haul—number notwithstanding—and the fact the nets are not torn (emphasized, in contrast to Luke’s strain and swamping [5:6-7]), suggest the sign is in any case a blessing, not just a sign of Jesus’ power but of the work they must now do. Raymond Brown sees the whole fishing story as obviously about the mission that the disciples will undertake. Unless we are reading it along with Luke’s fishing story, where call is the theme, and with the other synoptic “fishing for people” scenes, this isn’t quite convincing. The authors and editors knew the synoptic Gospels I think, but to imagine their first readers did and can read across as we might is a stretch. This encounter with the initially unknown and then unnameable one by the lake functions as an assurance of his presence, but its emphasis is more ecclesial or pastoral than missional, if this is a fair distinction. Jesus comes to offer encouragement when they are no longer sure of themselves, and the former life (?) seems to beckon.

The exchange between Jesus and Peter has an obvious symmetry with the three-fold denial of chapter 18:15-27 and constitutes a reversal of it that renews their relationship. The three questions and answers about love and lambs include a sort of rotation through vocabulary; while the most famous aspect of this is the shift in language Jesus uses for “love” (on which more below) note that the language Jesus uses for “feeding” and “tending” “lambs” and “sheep” varies each time.

In the first two cases Jesus uses the verb agapaō—related of course to agapē—to ask his question, and each time Peter responds with a form of a different verb, phileō, recognizable as a root still used in English. When Jesus then switches to phileō the third time he asks, matching Peter’s usage, this has sometimes been taken as a sort of concession, an acceptance of Peter’s limits. This assumes agapaō is the higher or stronger form of love, but this may be the product of reading too much C. S. Lewis. Others suggest that phileō is actually a stronger usage, at least for personal intimacy. Usage of the two in the main part of the Gospel suggests they are equivalent; Jesus for instance loves Lazarus deeply with both words (11:3, 5). So the change may be more a variation for the sake of literary style, like tending and feeding sheep and lambs.

The closing pronouncement of Jesus about Peter’s fate implies the readers know something of what had actually taken place later. While no details are given, this implication of martyrdom as the consequence of pastoral leadership also connects Peter’s fate with that of Jesus. Love is enough to incur such a fate. Once having denied, Peter would in time “follow” (v. 19) in deed as well as word.

The third episode in this chapter is not read today, i.e., an exchange with Peter about the fate of the beloved disciple, dealing in part with the difficulty of a belief that he might not have died (but presumably now had, like Peter). The association between Peter and John was already there at the empty tomb (20:3-8) so again this continues a thread in the main part of the Gospel. This adds to the sense that all these episodes at the lake were added in a conscious way, not merely as a sort of appendix but to answer some persistent questions and to tie up loose ends—or perhaps to point forward beyond these stories to others, and to help the reader realize that the story is not over.

The fish story, if not in the material available to the earlier author(s), was deemed important to add as the third (21:14) in a set of resurrection stories, and as a witness to the tradition about Jesus appearing in Galilee. Peter’s encounter with Jesus is both a resolution of the jagged edges that his story had left behind in the denial episode, but also a nod to what the author and readers knew, which seems to be his martyrdom. All this material also adds to the sense that the story is open-ended. The original draft had suggested the signs offered were a selection (20:30), and now the editor adds more. Through all these, not least the hints at the further stories of Peter and the beloved disciple, we are now encouraged to think that there were many more stories to tell, and to read the world itself as a book full of signs (see 21:25).