The lectionary does us a disservice by the omission of the first verse of chapter 10: “He left that place and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan. And crowds again gathered around him; and, as was his custom, he again taught them” (10:1). While this may seem just to be incidental detail, it is not; all that we will read from here on is part of the journey to Jerusalem that Jesus has twice foreshadowed in predictions of the passion in recent weeks. The ethical discourse that follows takes place on this journey and has to do with the community formed on the way to the Cross—and to the renewal of the world.

The little band have now made the portentous move from Capernaum and Galilee to Judea, the territory of Jerusalem, and much closer to the crucial events. Mark does also explicitly evoke something like the old Galilean atmosphere with the picture of crowds gathering, and Jesus teaching “as was his custom.” Yet that backward look is deliberate, and includes a sense of what has changed as well as what is familiar. The unfortunate result of the omission is that we may read as timeless and abstract what belongs to this urgent and conflictual setting.

We do read, at the beginning of verse 2 and the set Gospel reading, that this exchange about divorce is not merely a classroom exercise where Jesus holds forth generally about marriage, but a response to some Pharisees who came “to test him.” In Mark’s narrative this group have long ago decided to act against Jesus (see 3: 6). In other examples of this sort of interaction where people “test him,” Jesus clearly engages in a kind of repartee, understanding the nature of the question as hostile, and answers not to provide timeless case law but to give what was needed in the situation, often shifting the subject or assumptions in the process. Compare from earlier in Mark the Pharisees’ challenge about the Sabbath (2:23-8), or the occasion when they seek a sign “to test him” (8:11-12); soon enough we will read the trick question about taxes and Caesar, which has been badly misread for much of its history because the context was ignored (see 12:13-17). We should not be satisfied with any interpretation that does not make us ask about the real or supposed interest of the questioners, or that forgets that Jesus is on his way to the death and resurrection of the Son of Man.

These Pharisees open with the unlikely question of whether it was lawful for a man to divorce his wife. No-one we know of among the rabbis questioned this, but only the conditions under which it might occur. Commentators often point out that the controversy has yet another context beyond those we have noted in Mark’s work, namely a contemporary rabbinic debate about divorce between the teachers Hillel and Shammai and their followers. Hillel was the more liberal (in today’s terms), Shammai the more restrictive; yet it is a misreading simply to place Jesus on the restrictive side of a legal debate.

Jesus’ response, not unusually, is a counter-question, in this case concerning Moses (i.e., the Law). The Pharisees respond by referring to Deut 24:1, where the requirement of a document of divorce is specified. The point (in Deuteronomy) is not that divorce is allowed, but that such evidence provided the divorced woman with proof of her status, and hence a measure of autonomy and transparency, including her freedom to marry again. This was a matter of justice. Jesus’ comment that this was about “hardness of heart” does not contradict this, but notes that such legal protections assume the unfortunate possibility of oppressive treatment and lack of compassion without their provisions—but the same could be said of any part of the Law.

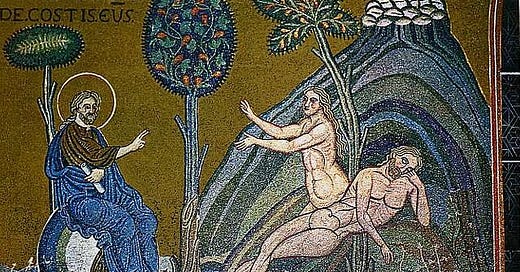

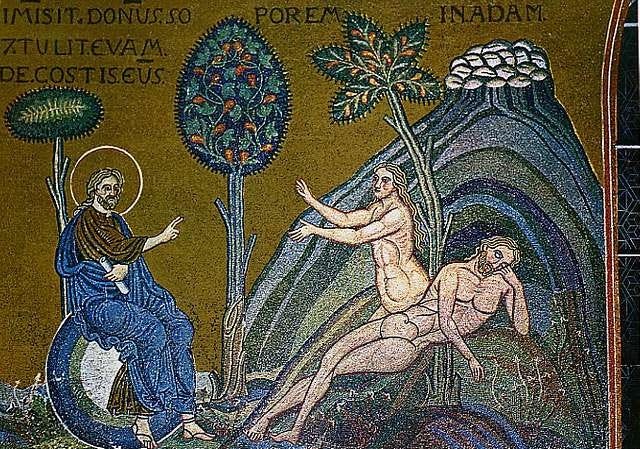

Jesus however evokes now a more fundamental level of divine order and purpose for marriage, and human social existence more generally, than the Law of Moses—which is that of creation itself. Genesis depicts God creating in an ideal way, but then afterwards interacting with fallible human beings developmentally or historically to set achievable and appropriate limits for their behavior as they struggle, with the Law as a sort of end point. God’s provision changes in response to the demonstrated capacity of people to behave in certain ways. Not only is divorce originally absent in that “beginning of creation,” so too is violence, and property, and so much else. All of the specific laws that come to greater definition across the narrative of the Pentateuch, and especially in the covenant made with Moses, are examples of the same kind of concession and boundary-setting that responds to human limitation and failure, and seeks to ensure justice.

The Law of Moses provides (just as for those other issues) a workable way for Israel to deal with the complexity of real life, and to maintain social order in the somewhat messy world known to us in history. Yet Jesus still insists on foregrounding the original and ideal vision of the creation of human beings, and the intimacy of mutuality in the Genesis creation story. This suggests that his own call to discipleship does not contradict the Law, but is not content to rest on its historic compromises either. The way of the Cross and the “ethics on the road” to which the disciples are called involve a renewed world, and so focus again not merely on what we have become used to amid the messy reality of life, but on God’s good purpose in creation.

By implication then, Jesus signals that the reign he comes to bring is a renewal of that primordial ideal, without divorce of course, but also without violence and injustice generally. His conclusion to the Pharisees that “what God has joined together, let no one separate” is not about legality, or even solely about marriage and divorce, but the call of God, once in the beginning and now again through him, to live in a wholly different way. To “separate” human beings from their intended relationships of course refers to marriage, but also implies any situation where we fail to recognize the mutual dependence and love intended in creation.

Jesus does then speak, separately and to the disciples, directly to relational disruption, offering Mark’s readership something closer to concrete ethical instruction. This is of course a teaching against divorce, but Jesus now grounds that more concrete position both in creation but in a vision of justice, and of human relationships shaped by more than law. Most striking here may be the gender equity with which he addresses the question, making women agents in such situations where the Law of Moses had seemed to treat men alone as the ones whose power and choices prevailed, and had to be controlled.

While this level of female agency may also have been more in keeping with Roman law (perhaps as known to Mark’s readers) it seems to roll back a patriarchal set of assumptions that belonged to that intervening historical mess to which Moses’ rule was addressed. Yet even while holding all accountable to a renewed vision of God’s intention for intimate relationships, Jesus does not pretend that divorce will not happen. The call to live differently on the way of the Cross is never presented as a criterion for casting aside those whose lives have not perfectly reflected the goal, but rather as an ideal towards which the road is leading us.

Just as the discussion about divorce reflects not a mere quest for rules, but a focus on the nature of God’s reign and the call to follow Jesus with urgency, the next scene with children being brought has more to it than children’s place in society, but concerns the nature of human life in the renewed world that God’s reign entails. It is no accident that after marriage come children; the episode continues to reflect the difference between the ethics of the present world and those of the coming reign.

After having affirmed the dignity of women in a way that reflects the original creative purpose applied to the present world, children now feature as a vulnerable group who suffer unduly in the world of unjust and unequal power. Again the hapless disciples—the wayfarers following Jesus on the road— are getting this wrong, and act as the foils for the issue at hand. It may be relevant to the previous discussion also that these, who are undeniably closest to Jesus and beloved by him in a unique way, function primarily as examples of failure and incomprehension. They “rebuke” those bringing the children, which is just the same language (NRSV “spoke sternly” doesn’t help make the connection) used for Peter’s and Jesus’ mutual rebukes in the key scene (chapter 8) when Jesus had predicted what is happening now, this journey. So they are, like Peter, denying the nature of the road they are on.

This is not about infant baptism or any similar issue (although one reasonably could make arguments based on it). We noted recently when discussing the disciples’ concern for greatness, and the way a child featured in that scene, how children functioned as a sort of test and example of how the reign of God is different from the world against whose order and power Jesus witnesses. Yet while Jesus here affirms that the reign of God belongs to such as these, his final act in the scene is not to present them as pedagogical examples, but to receive them concretely and personally, blessing them. All those whom we encounter on the way are more than objects for moral judgement, or signs for edification, but companions on this journey to a new world, where we see again that all created by God is good.

Thank you, Dean. I appreciate your insights and the context of them being in Judea. And the Pharisees! Plus ça change, plus ça meme chose...

Words in my brain are: love, covenant, vow, relationship, honor, integrity, justice, mercy, commitment - all are suited to "marriage," and all are suited to other human undertakings, such as baptismal vows, oaths of office, promises of actions to be taken ... to keeping our word as we trust God to keep God's. Marriage is, in this instance, a metaphor for a life lived honorably in all aspects, and not least in our relationship with God.