…and as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.

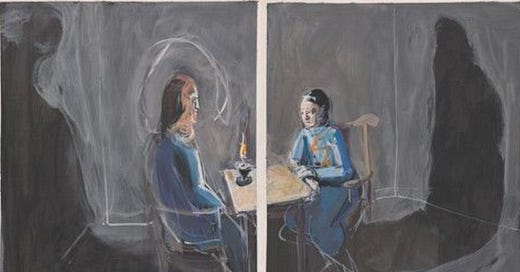

This Gospel is an excerpt from a conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus, who “came to him by night” (3:2). The verses we read however do not provide this context. The lectionary illustrates how John at times lets narrative and literary frame fade away as the voice of Jesus starts by interpreting an event or an initial exchange, but then seems increasingly to speak outside of time and space, and to the reader rather than to those present in the text. By the end of this excerpt, Nicodemus has disappeared; even the famous statement made along the way about being reborn is addressed to some plural “you” (v.7), for whom the scene is now being played out, rather than in the intimate one-one exchange that was introduced.

Contextualizing here doesn’t just mean starting with Nicodemus’ arrival for conversation at 3:1, since this episode flows on quite directly from the Temple incident we read last Sunday. The last few verses of the previous chapter, bridging these two sections, were these:

When he was in Jerusalem during the Passover festival, many believed in his name because they saw the signs that he was doing. But Jesus on his part would not entrust himself to them, because he knew all people and needed no one to testify about any person; for he himself knew what was in a person (2: 23-25 NRSV, adapted).

The Nicodemus scene then begins (literally) “a person of the Pharisees.”1 So Nicodemus’ visit exemplifies this position of someone “believing in his name” (2:23) but not warranting Jesus’ trust. Nicodemus has come with an agenda; not a malign one, but somehow the wrong one nevertheless, wanting information, even though what—who—he needs is in front of him.

Nicodemus believes Jesus has “come from God” (3:2), but Jesus responding implies Nicodemus doesn’t really know what that means, or how to read those “signs.” This incomprehension is clearest in the famous exchange about being born “again,” or “from above” (vv. 3-10) —which, ironically enough, is as misused and misunderstood in contemporary Christianity as it is by Nicodemus.

The issue that spills from this narrative frame into today’s Gospel is what “coming from God” (or “from above”) means. Nicodemus is an “evidence-based” sort of person (cf. 7: 50-52). The “signs” Jesus does lend him authenticity as a divinely-authorized teacher who will apparently offer guidance and instruction, bringing wisdom “from above” to the human realm, but not changing the relationship between the two. This idea of a divine revealer going up to bringing information down had some currency in theology and philosophy of the time. Moses, Enoch, and Elijah were all sometimes thought of as revealers who had ascended into heaven to disclose divine secrets to mortals below when they returned.

Jesus turns this interest in ascent and descent, the above and below, on its head as our Gospel reading begins.

and just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.

It is no wonder the second part (yes, “John 3:16”) is so often quoted separately—to mixed effect—because the image in the first is so dramatic, and complicates it. Bronze serpents? But these sentences need each other. Jesus’ being “lifted up” refers here of course to the Cross, of which the serpent (whose story is also told today from Numbers) is taken to be a sign. Yet his version of being lifted up also amounts to a critique of the conventional ideas about heavenly beings or revealers ascending and descending calmly and benignly with their stores of divine knowledge.

Jesus has asserted his uniqueness as one who links heaven and earth in v. 13, immediately before we start reading: “No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man.” Our Gospel then ignores an “and” which links its opening statement to this one; the whole sense is really that “Jesus is the only heavenly revealer, and is showing you that this means something quite different from what you have assumed.”

Jesus rejects the idea Nicodemus brings, of the divine revealer as a sort of pedagogue who will share interesting theological tidbits and diverting signs from the upper realm. The point of ascent and descent is not information, or even edification, but salvation. Yet Nicodemus has already faded from the picture; the one to whom this lesson is addressed is now the present reader.

The suggestion that the Cross mirrors the lifting up of the serpent is a radical reinterpretation of Jesus’ death, rather different in specifics from ideas based on sacrifice or ransom doing the rounds at the same time, but sharing with them the startling claim that the death of Jesus was far from what it seemed; in this Gospel more than anywhere, it is a triumph (and here it is also a source of healing in particular, cf. Numbers)— not tragedy.

As well as re-interpreting the Cross, Jesus reinterprets the relationship between earth and heaven. That Jesus has “come from God” is less a sign that there is a realm above, or that its wisdom can be received by attentive sages, than that God has loved the world in a particular way. Jesus’ ascent will not take the form of a serene heavenward journey; it is the Cross that constitutes an unlikely exaltation, a triumphant return to the Father. On the Cross, he fulfills the work of a savior who was not merely content to descend, but by being lifted up has saved the world.2

I owe this connection to José Porfirio Miranda, Being and the Messiah: The Message of St. John. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1977.

See on this John Behr, John the Theologian and His Paschal Gospel: A Prologue to Theology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019.