We resume the broader narrative of Luke’s Gospel for the first time since March. Although the story of the man inhabited by a “legion” of demons (who end up in a herd of swine) appears in all three Synoptic Gospels, this is the only time it is read in the three years of the Lectionary. Mark’s and Luke’s versions of the story are very similar; so we are in a sense dealing both with Mark’s and with Luke’s edited version.

Luke has done a few things—reflecting his concern for an “orderly account” (1:3) —that aren’t likely to make it to a sermon, adapting the story mildly to make it somewhat easier to read. He introduces earlier in the piece the background details of the man’s dress and abode that we only pick up along the way in Mark, and moves details about ferocity and chains into a later parenthesis, where Mark had begun with them. The basic narrative though remains unchanged.

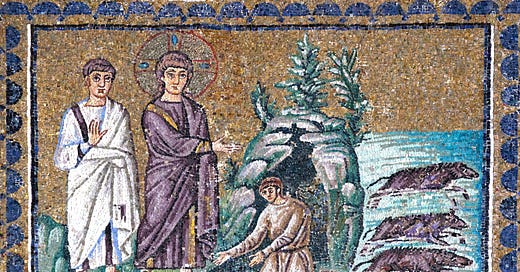

Jesus and the disciples have just crossed the Sea of Galilee (during which he has also calmed a storm), and have now arrived in territory which is geographically and otherwise distant from the Galilean homeland. So Luke’s pithy term “opposite Galilee” constitutes more than a map direction. The episodes that had preceded this story were set in Galilee (and Judea), but now Jesus and the disciples have entered a different realm where, it will become apparent, both gentile and demonic influence are evident. This is alien territory, and as we will shortly see, occupied territory as well.

The man who is possessed is deferential to Jesus; Mark had even said he “worshipped” (literally, prostrated himself to) Jesus, but Luke is a little more guarded, saying simply that he “fell down before him.” While the demons are enemies, they consistently recognize Jesus’ authority. The man now addresses him (Luke retains Mark’s phraseology here) as “Son of the Most High God.” This also sounds deferential, but the term has a curious ring to it. This is not a typical way to refer to the God of Israel in scripture, but is used (e.g.) for the ancient (non-Israelite) priest Melchizedek’s ministry, while another possessed Gentile who appears in Luke’s second volume (Acts 16:17) similarly calls Paul servant of this “most high God.” While accurate, the title implies a non-Jewish setting.

While the man (or his collective possessor) speaks first, we learn that Jesus had (wordlessly, we assume) already commanded the spirits to depart by the time the action begins. When Jesus does speak aloud and asks the demon its name, we should not imagine he needs to know the answer; it is given for our benefit, both to show the demons’ compliance but also for our reflection.

The answer is “Legion.” Mark’s slightly longer version (“My name is Legion; for we are many”) might distract from the core of the answer; they are indeed “many,” but there are plenty of ways a large number could be conveyed—a crowd, a flock, a herd (see below)—without using this loaded and very current term in occupied Judea. Luke lets the single-word answer resonate in the scene and in our minds. It is deeply sinister.

Roman legions—which were made up of 4-5,000 solders— had marched into Judea almost a century earlier under Pompey and had been there ever since, even when Herod had ruled as a local puppet. Roman power was “order” in the minds of its practitioners, and chaos in the real lives of those on whom it was imposed. Legionaries were a constant presence and threat to the local population, a reminder of imperial subjugation. The Roman occupation was a concrete form of oppression, and also an embodiment of pagan and gentile affront to Israel’s loyalty to its true ruler, the Lord God. Jesus’ encounter with this demonic army is thus a skirmish between two forms of order and power.

“Legion” therefore is more than just a crowd. This man has been invaded by an army sent unsolicited by the forces of evil, purportedly to bring order, but in reality to cause chaos, as his plight makes clear. At the very least, this is a metaphor that relies on knowledge of the foreign occupation and its attendant forms of oppression in showing the man’s suffering. Yet it is more than an image; as well as being an unguarded description of demonic influence in the life of the man himself, it is a protest against the occupation and how it compromised and competed with Jewish identity and faith. The realm of the demons is not merely interior, but social and political.

The geographical and cultural markers in the text that emphasize the gentile territory are interdependent with the appearance of “Legion.” The address by the demoniac of Jesus has already been noted, as has the location of these events away from Jewish life, and then eventually there are pigs (more in a moment) which will add to the sense that all this takes place outside the Jewish sphere. Luke does not however “demonize” the gentiles themselves; the man Jesus delivers from occupation is himself presumably a gentile, and for that matter before this point in the narrative we have seen exorcisms and other forms of struggle with evil take place in the Jewish realm too. Rather we are being reminded that the mission of Jesus involves deliverance for all, and liberation from all that compromises human life in its fullness, in whatever sphere.

Yet the demons—sounding like occupying forces all the more— beg that they not be expelled and sent home, as it were. They want a procession rather than a complete withdrawal. Jesus’ agreement suggests this is a battle and not the end of the war; evil has not yet run its course. We do also have to note the swine. Their presence is of course part of the gentile scene-setting, given Jewish avoidance of pigs and pork. Their fate probably attracts more attention from modern eyes than from ancient ones—which is ironic in an era when we allow such horrifying treatment of pigs in factory farms— but the point here is just that the demons themselves continued to wreak havoc. Jesus does not determine the actions the demons choose next, but they continue their imposition of chaos. We must accept that for Mark and Luke clearly the man’s deliverance is given more significance than the fate of these (unclean) animals.

Discussing Mark’s version, Ched Myers points out that the possessed pigs’ behavior continues the legionary image, and his points apply here too; when Jesus “gives permission,” sounding like one who has taken over command for a moment, they rush off as though attacking. Even their “herd” is possibly a military metaphor, used for groups of recruits (bear in mind that pigs do not flock the way sheep or goats do).

The final scene has the man now saved from the national guard of evil presented as a model of peace, clothed and in good mental health. This simple picture juxtaposes the real order that comes from God’s love with forms of supposed order imposed by the structures of self-serving power. The man also seeks integration into Jesus’ forces, but even in Luke’s inclusive view the presence of gentiles in the movement is for later, and comes in the second part (Acts) of the story. So it is remarkable that even now Jesus allows the man to spread the good news about him in a gentile setting. A new order of nations, a new way of seeking peace and using power, has appeared even beyond Judea and Galilee.

—

Further reading:

Johnson, Luke Timothy. The Gospel of Luke. Sacra Pagina 3. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1991.

Myers, Ched. Binding the Strong Man : A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. Maryknoll, N.Y. : Orbis Books, 1988.

I find it so interesting that when Jesus rejects this man's desire to join up, He tells him to "Go and tell what God has done for you." This mission statement cannot include, "He died for my sins and raised again on the third day." I am often sad that while this climax is vital to our faith, we negate so much the entirety of Jesus' ministry and whole-ness making work by boiling it down to only these climactic actions - instead of seeing it as a continuation of the work that "The Most High God" has always been doing since Adam and Eve and the promise of redemption.

I have always thought that the name "legion" was a direct reference to imperial occupation, but your description of it here with the backdrop of "legionaries" is SO helpful. Thank you! And I am also struck by those who point out that many of the symptoms of those described in Gospel accounts as being possessed by demons are very much akin to what happens to those who are occupied by colonizers, including severe social isolation. Jesus telling the man to go home and back to his community is in that sense part of his healing and restoration, a "remedy" for "colonized syndrome." Thank you, Andrew!