Death seems unavoidable this week. Paul’s Letter to the Romans provides the starkest rendition of baptism as solidarity in the death of Christ, and the collection of sayings in the Gospel (extended from the Roman version from vv. 26-33 to this long reading) foregrounds conflict, suffering, and death leading to its climax: “Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.”

If this isn’t a problem for the preacher, we probably aren’t paying attention.

While we are becoming clearer about the decline of religion in the contemporary West, there are qualitative changes to how religion works that are just as fundamental and problematic, and I suspect less well acknowledged. The privatization of religion is one way of talking about it that mostly still works; where “religion” in the ancient and medieval worlds still referred to how all of life, including familial, political, and social practice generally, were understood in relation to the divine and its demands, our idea of religion begins with the interior life, and often seems to have a hard time getting out of it. A fairly common view among our own adherents is that religion—or (worse) spirituality—is one part of life, important to get right along with other things to which it bears no very profound relationship. Diet, politics, sex, vocation, finance, and so forth all have columns on the great spreadsheet of life, governed by their own logic.

In this view there can only be minor leakage from one column on the spreadsheet of the well-balanced life to the other, and in fact the genuinely “religious” aspect, in the sense that Jesus or Paul would have seen it, is veiled here; for what is non-negotiable, what really guides our lives, often isn’t what comes from the religion column, but a broader and typically unexamined notion of happiness or success which avoids suffering and ignores death.

This problem—it is a problem—isn’t quite the point of the Gospel this week, but it’s close, and the Gospel certainly offers a vision of life following Jesus that is wildly disruptive of the well-balanced bourgeois version of faith and spirituality.

The collection of sayings has some specific Matthean features; some of these are found elsewhere in the Synoptic tradition, and one—the remarkable “whoever finds their life will lose it, and the one who loses their life for my sake will find it” (10:39) is paralleled only in John. Here in Matthew though, the teachings proceed directly from Jesus’ instructions to the twelve; yet whereas the part we read last week was quite concretely related to their unique mission, much of this material is couched more universally—which is sobering, since so much of it is confronting. This feature is what has drawn it together for the evangelist’s purpose; the call of the Christian is not to false comfort, or to substitutes for what is truly important, even things that seem good in themselves like family and prosperity, but to a radical gift of self that corresponds (as far as we find ourselves able to give it) to God’s own gift.

Three times in this collection the question of death arises as a possible (likely?) consequence of discipleship:

Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell (28)

[after the saying about loving family more than him]…and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me (38)

and then the saying shared with John about losing and finding life already quoted. These are deeply discomfiting. They are of course accompanied by words of profound reassurance; but the assurance isn’t how we would probably want it, like “don’t worry, it’ll never happen.” It’s more like “yes, it will happen and it doesn’t matter”:

So do not be afraid; you are of more value than many sparrows.

Everyone therefore who acknowledges me before others, I also will acknowledge before my Father in heaven

And then, once again, the saying about losing life and finding it. This isn’t quite the Purpose Driven Life, let alone the Power of Positive Thinking. And let’s not talk about Joel Osteen.

The call to radical discipleship, to be ready to abandon whatever stands between us and faithful witness, haunts us, and rightly so. And if this is not preached, woe to us all. Someone will need to hear it. What these sayings all share though is the perspective that what is apparent now about our lives and their success bows to a perspective that is eschatological; that is, that God’s ultimate resolution of our lives, including the ways suffering and injustice are resolved, are not limited to the obvious or material present.

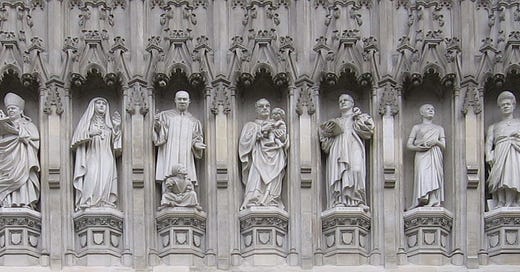

Part of the cost of the “spreadsheet” synthesis is how poorly it equips us to think about suffering and death. What passes for God’s action in that view tends to be feeble and cheery, only to be claimed when things have gone right. Those whose faith has endured to death without obvious redemption, or those whose faith has even led them to risks that have brought suffering and death—Esther John, Janani Luwum, Paul and Peter—have no place in this view, except to foster the regret that their worthy moral examples were cut short. The Gospel dares us to consider instead the possibility that every life lived fully aligned with its own promises, long or short, and especially those lived without regard to the apparent cost of living that way, are triumphs, not tragedies.

In both the call to radical discipleship and in the possibility offered of knowing God’s presence even in death, there is a challenge here to take utterly seriously the fact that God is more than an abstract force for good, but the mystery of the world whose love we can barely comprehend, and in whose world we can thus live without fear. You are worth more than many sparrows—take courage, and you might even gain your life.

Thank you once again Andrew.