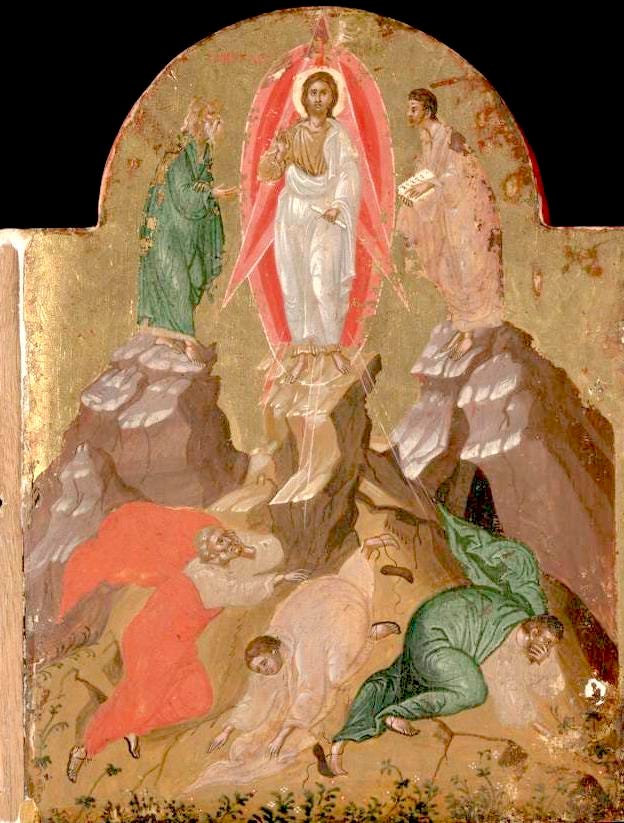

We now jump from the early part of Mark’s narrative into the middle, given the lectionary’s use of the Transfiguration story every year on the Sunday prior to the beginning of Lent. While this rapid shift (intended as a sort of climax to the “epiphanic” themes of the post-Christmas period) disrupts our progress into Mark’s story, it does provide a key example of this Gospel’s literary and theological character. The Transfiguration story is part of a central hub around which the whole work turns, a pivot from Galilean ministry to the fateful Jerusalem journey.

The most challenging thing about preaching Mark’s Transfiguration authentically may be the omission of this context, especially the immediately preceding episodes (8: 27-38). In a dense few verses prior, Jesus had asked the disciples about his identity, and Peter famously confessed him as Christ, but then tripped badly over Jesus’ immediately-following prediction of his suffering and resurrection —which then leads Jesus to tell them of the necessity of the Cross, and the fact that “those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it” (8:35).

Peter’s confession was the clearest instance so far in Mark of a human actor discerning Jesus’ identity, yet Peter’s understanding of Jesus as Christ was also shown to be worse than inadequate. Previously (as we have seen) demons are the primary bearers of this information, and now Peter himself is labelled “Satan” as he joins in the chorus of those who think they know the answer, but have not really pondered the question.

The Transfiguration story follows this exchange and is a further—in some ways definitive—statement about Jesus’ identity and the nature of discipleship. Preachers cannot perform much of this contextualization relative to the end of ch. 8 explicitly, but this story itself includes the themes of misunderstanding, and of the necessity of Jesus experiencing the cross before his glory can really be known. This can, or must, be foregrounded for us to be preaching Mark and not just some abstract idea of Transfiguration.

What sort of story is this though? In what we have read of Mark the baptism story resonates strongly with this one. Both are revelatory moments, but apocalyptic and not merely informative ones; the power of God erupts into the narrative not merely to share information but to reorient us.

In both cases, this divine power is not the institutionalized divine glory in the Temple, but occurs in a remote place which echoes the experience of Israel in its journeys from enslavement and exile to freedom. At the baptism, Jesus had been revealed by the divine voice as “my Son, the beloved,” but was himself the only witness. Now the same voice uses strikingly similar language, but presents the beloved Son to the onlooker with the command “listen to him.” It is now time for them (and us) to see and understand who he is in a different way.

Moses and Elijah help to reveal Jesus’ particular glory, the essence of what the divine call to “listen to him” really means, in ways that can also help with the problem of context. In a wider sense, relative to Israel’s whole story, they are the context. They do represent the law and the prophets as is often said, but their own “mountain top” experiences (see Exod 33 and 1 Kings 19) also involved rejection and misunderstanding. They are witnesses to the same glory, of a God whose involvement in human life will often call us to struggle against what is expected.

While visionary experiences like those of the mystics may be relevant to understanding the event, Mark does not really present the Transfiguration as remarkable because it is a striking vision, but because of what the vision conveys. In what Morna Hooker calls this “God-filled universe” of this Gospel, the fact of divine appearance is in itself far less vexing, and hence less likely to distract from the specific message. As readers of the Gospel, we are being challenged to consider the identity of Jesus and the content of the message, rather than to analyze religious experience.

The idea that the story is somehow a displaced resurrection appearance was often mentioned in 20th century scholarship. I suspect we would be doing Mark an injustice by imagining all this was the result of a cut-and-paste gone wrong, but there is an idea worth pondering here, especially when we consider the lack of an appearance story in the oldest text of Mark, finishing at 16:8. If that version of Mark is an “original” of sorts—we cannot tell—then this gives the Transfiguration story a different significance, not as a displaced story so much as an anticipated one.

Those present encounter Jesus’s divine glory, but when Jesus and the disciples come down from the mountain he warns them—characteristically—not to share the vision, but now has a more specific instruction about timing: it cannot be shared until after the Son of Man had risen from the dead (v.9). So what they had seen could only make sense, could only be understood properly or shared, after the resurrection. It is a story for the resurrection, if not of it.

The Transfiguration is thus a glimpse into the future, rather than a piece of esoteric knowledge for the disciples to enjoy. It entails the same message of a Gospel whose nature is as confronting as it is glorious, and which remains mysterious to others, as has been consistently depicted so far.

The command “listen to him” is simple in itself, but just as the earlier references in Mark to “the Gospel” and “the message,” or to Jesus’ seemingly oblique teaching, may seem baffling initially, the idea of “listening to him” is not just absorption of information. We could add Gospel to Law and Prophets and be no closer if all, if we only meant the words in question. Listening to the beloved can only be fulfilled in the act of following him.

Just discovering your substack. Thanks for this post. It really helps with my pondering about "why do we need this story?"

Thanks, Andrew. Looking forward to preaching this. Very helpful to have the Mark context here.