Sacrifice, Slavery, and the Promise of God

Proper 8 Year A; Gen 22 Gen 22:1-14, Psalm 13, Rom 6:12-23, Matt 10:40-42

The famous story of Abraham and Isaac featured in the Track 1 Old Testament reading this week (if you’re not reading this, bear with me), is not about sacrifice.

Now that I have your attention, let me put that a little more subtly: this story is about sacrifice in the sense that the Noah story is about navigation, or the Parable of the Sower is about agriculture. In none of these cases is the named element the point of the story. Admittedly it is hard, and perhaps impossible, to treat that element as just a neutral medium. My opening statement then needs to be qualified: the flood, the seed, the knife, are more than incidental, yet neither are they the point.

The story makes use of the premise of child sacrifice—a known practice in the Ancient Near East—to tell a story about faith. Child sacrifice itself was at most an extreme and unlikely prospect in Israelite religion when this text was written. Some have even seen this story as a narrated critique of the practice, but perhaps, like the story itself, such awful possibilities were only an ancient if yet potent memory in Israel.

And yet the horrifying prospect at the center of the story never takes place. Isaac was not sacrificed. This is not, then, a story about sacrifice. So what is it about?

Before we answer that, people still balk at such a practice being even the unperformed premise of a story. What about the horror of child sacrifice itself, and of course the (apparent, reversed) divine mandate for it? A similar concern could affect how we read the Epistle this week; there will be readers disturbed at the ready use of slavery as a metaphor for our being in God, rather than an object of resounding criticism. Neither the Yahwistic writer from or through whom the Abraham story comes, nor the apostle Paul in Romans, takes the time we might wish to focus on the problematic idea in question and critique it.

As a result there is now a genre of preaching which goes something like this: the scripture we are reading today refers to something very bad, this thing has done great harm, let us all rise up to oppose this harm.

This represents something less than actual preaching, although it might be an important step in the interpretive and even the homiletical process, a moment along the way however, rather than a conclusion. Of course slavery is wrong, and so too is child sacrifice. In the former case at least yes, too many (white) Christians were silent, complicit, etc., for too long in modern western history and this should not pass unremarked. Perhaps one can also work from the implied availability of young Isaac for ritual murder to (say) the many sins of commission and omission on the part of the Church with regard to children, less direct as that connection may be.

It is not wrong to take opportunities to name such misuses or lost opportunities, but to preach or to read scripture must be more than bemoaning other’s faults, whether those attributed to Abraham or those committed by earlier interpreters (One of the ironies of this primarily moralistic discourse is that it rarely stops to wonder about its own lost opportunities or overlooked false premises).

We dare nevertheless to suggest there is good news here, and the reader is invited to find it even among the wreckage of these interpretive and other failures.

The Genesis story is not really about sacrifice. It is, as interpreters Jewish as well as Christian have long known, about faith. This may not be quite enough either, though. I suspect we have all heard sermons marveling at Abraham’s great faith in terms something like “his willingness to give up what was most precious,” which is often how modern ideas of sacrifice are couched. This is not what sacrifice meant in the ancient world. Gifts of food—bread, vegetables, and of course animals and their meat—were regularly shared between worshippers and the deity as a sign of their relationship. Sacrifices could be for celebration, for thanksgiving, to mark festivals—and of course sometimes to repair the breaches of those relationships, as acts of atonement.

We moderns have changed the word “sacrifice” because of this story, and because of the story of Jesus, neither of which is a sacrifice in straightforward terms—Jesus’ death was a judicial murder, not a religious ritual—but which our forebears interpreted as though they were sacrifices, looking for meaning beyond cruel demand and brutal death. Thus we have been bequeathed the notion of sacrifice as altruism, the willingness not to share but to suffer. This is a mixed blessing, but not today’s topic.

Abraham’s challenge was not however to “give up something special,” it was to trust that God, who had promised Abraham that all the families of the earth would be blessed in him (Gen 12:1-3), would fulfill that promise, despite now threatening to negate what had already been done to achieve it in Isaac (see the last three weeks’ readings).

This doesn’t really get God off the hook, to be clear. God is not offered in this story, or in scripture generally, as the impeccable but distant source of worthy moral imperatives (towards which liberalism’s doctrine of God usually devolves), but as the one whose promises and demands will often not be as we want, but which will never fail us.

To receive this story as good news is thus hard—no harder of course than receiving the Cross as good news. And yes, of course there is a deeply disturbing element in both stories, namely the possibility that God’s action in the world can somehow catch up into itself, not condoning but redeeming, actions and motives and consequences that in themselves we find impossible to accept. The way scripture works is rarely to offer neat propositions for our assent, but rather to present confronting possibilities for our transformation.

Sacrifice is the premise rather than the point, but Isaac and the promise are not negotiable in the end, even though Abraham is led to wonder about that for some time. The little ones are always God’s unswerving concern. In the Gospel, Jesus concludes the long instruction to the disciples with a set of promises, simpler than those to Abraham, but striking in their very simplicity: “whoever gives even a cup of cold water to one of these little ones in the name of a disciple-- truly I tell you, none of these will lose their reward.”

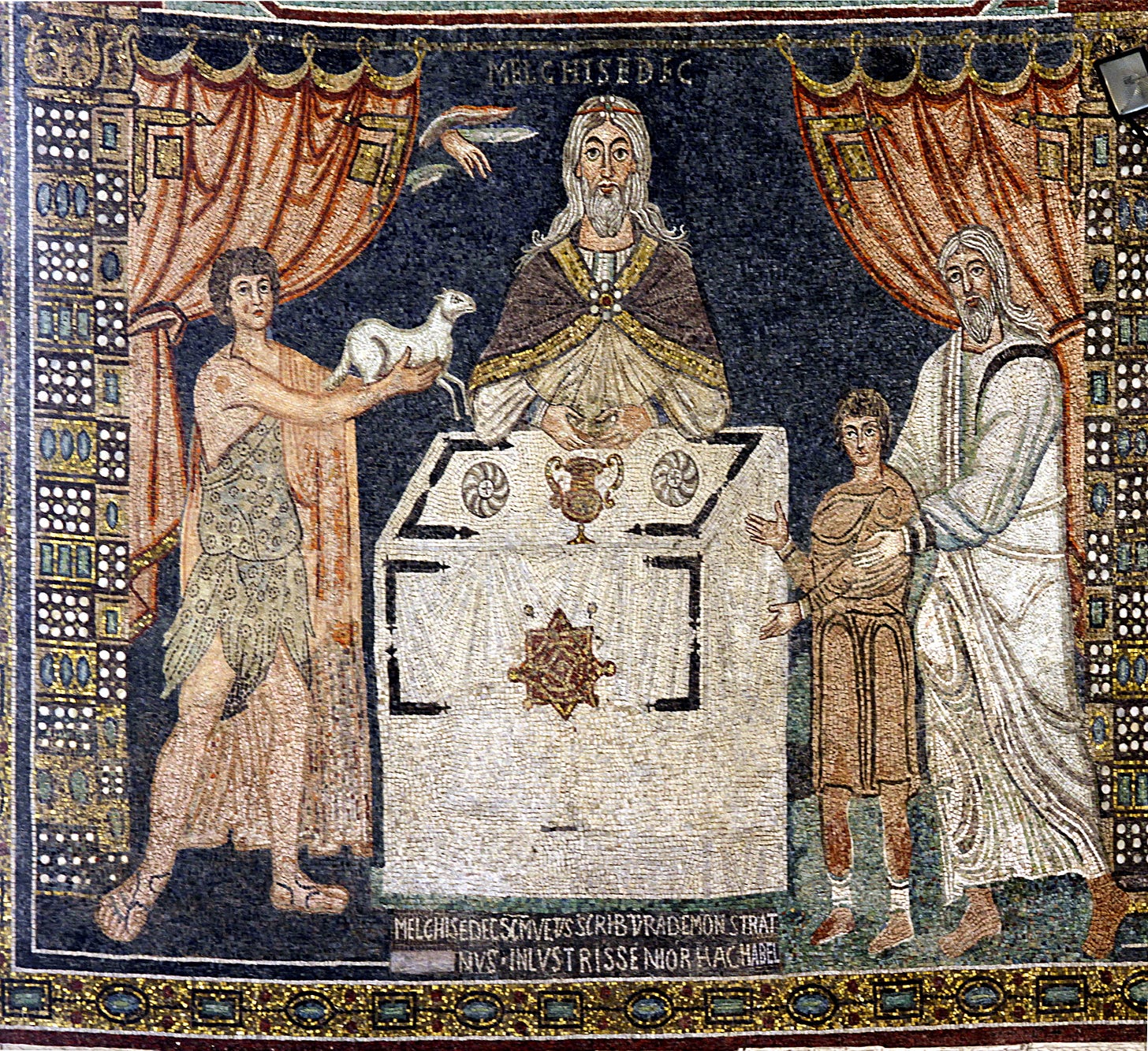

The image above shows Abraham and Isaac at a different altar, along with Melchizedek (Gen 14:18) and Abel (see Gen 4). These are all subjects of stories about offerings and sacrifices, their true meaning here shown not to be the deaths, real or threatened, or the suffering and loss, but the promise. The Eucharist evokes the promise for us, and calls us to embody it in our hopeful journey to the place where all are free, and where none are dispensable, or the mere object of others’ greed.

With Abraham and Isaac and Sarah, with Abel and Cain, with Melchizedek, and with the Psalmist, may we then find ourselves able to sing:

I put my trust in your mercy; * my heart is joyful because of your saving help.

I will sing to the Lord, for he has dealt with me richly; * I will praise the Name of the Lord Most High.