The second of three final parables from Jesus’ last discourse in Jerusalem is the familiar Parable of the Talents. The three are grouped together for good reason; as often in Matthew, a set of parables has strongly-related themes, and some of what is learned from last week’s wedding feast is relevant here. So too, this parable will contribute to understanding the final judgement next week.

In all these cases, readiness is crucial, but is not constant anxiety about getting the timing right, but the realization of the challenge and opportunity to prepare now, regardless of when or whether the crisis arrives. This setting in Jesus’ final discourse strengthens that theme of readiness and crisis, relative to Luke’s version (19:12-27), where the theme of reversal (cf. 19:26) is arguably stronger.

Talents, at least to begin with, are of course not creative traits or abilities, but sums of money. A talent is a very large sum to most people in the world of Matthew’s text, an amount that the characters in the Gospel (other than kings, tax collectors, and parabolic absentee landlords) would not usually see, let alone own. Remembering our earlier ponderings about the denarius, this was the equivalent of 6,000 of those, so these are amounts that the poor could only treat as fantasy, and the rich as really serious.

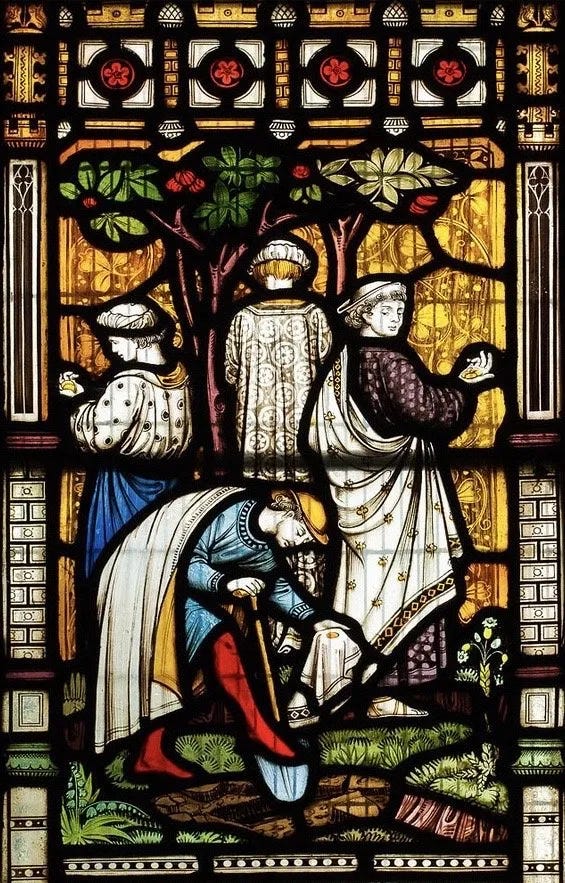

This parable seems to be victim of some anachronistic readings. We need to develop skills to read ancient texts in ways that attend to genre, and to history itself. While the details are interesting and potentially revealing, we should remember that images belong to that world not this one, and treat these historic features differently from the point being made through them.

Some readers on the fundamentalist side seem to read this parable as a defense of capitalism, because the slaves approved by the master are those who generate wealth—this despite the fact capitalism didn’t actually exist in the ancient world, although obviously trade and investment did. That the servants who receive commendation made money does not actually constitute an endorsement of any investment or business development strategy, or even of money, any more than the Parable of the Sower commends subsistence agriculture. The parable is not about its imagery, but about faith and practice.

Yet imagery matters. So when the parable also assumes—as a number of others have, this year of Matthew in particular— the institution of slavery, some readers will balk, and indeed perhaps all should. The question is what we do in response. While some seem to think that avoiding mention of offensive concepts and terms constitutes political action, the discourse of Jesus tends to take things head on; we could say that avoiding these challenging words and stories is burying this opportunity, rather than using it.

The possibility that reading the parable could normalize slavery is worth noting critically, but constitutes a task for the preacher, not a basis for avoiding the passage. Parables can be challenging, and their assumptions either attractive or discomforting, but the assumptions are rarely the main point. We must, Matthew’s Jesus tells us, be ready.

Yet if we are tempted to think that proper interpretation depends on our distancing from the world conjured by the text, in fact this parable (and its Lukan parallel even more, perhaps) actually adds details that are already intended to create some critical space between the imagery and the message. This scenario is unappealing in ways far beyond the mention of slavery.

The master does not correct the slave’s observation that he is a “harsh man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you did not scatter seed”; the master is clearly not God, but just a predictable landowner of the time.

To Matthew’s readers, close to a world of colonial dispossession and the creation of estates by wealthy parasites, the mere fact of an absentee landlord doling out massive quantities of money to his enslaved subalterns is (to borrow a modern image now) a sort of Trumpian nightmare.

Yet if the nature of the world and the characters depicted in the parable is confronting, they are still not its main point. The slaves are judged on what they have done with what has been given them; so, Jesus, says, will all be. What is it that we must do?

The presentation of that lop-sided world, where unearned wealth piles up (or gets buried, where it does nothing for the hungry any more than for the master) even as other characters often seem to wonder how they will earn and what they will eat, may be a hint. We are asked not just whether we are using what God has given us in some way or other, but whether we are using it for the tasks set before us.

At the risk of offering a spoiler, next week’s Gospel—the passage immediately following this—will be the parable of the Great Judgement, where the fate of those who meet the King will be determined, not by their business acumen, but by their compassion and generosity. Commerce is an image in this case, but love and justice are the message in that one.

We cannot praise or blame the medium of the Parable of the Talents but ignore the explicit teaching of that following climactic story, that makes clear that justice and charity are not merely good, but the acid test of discipleship. To enter into “joy of the [true] master” will indeed require attention to how we use what we have; this parable suggests, in a subtle and critical way, what are some of the problems to which compassion must be addressed.

The real way to achieve a lasting return on investment will be restated thunderously next week, but was already given in the Sermon on the Mount (6:19-21); where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.

Andrew,

I find that this parable still leaves a strange taste in my mouth. There's a pressure to be productive in here that resonates with a capitalistic, profit seeking motive. I think that resonance is a confusion for theft of surplus for the sharing in our collective earnings. Still, the discomfort is there and shows the way capitalism warps us and our ability to read the Gospels.