The form of the Beatitudes in Matthew’s Gospel is much more familiar, so this Lukan version needs to be brought out from under the shadow of its textual cousin. Luke’s “Sermon on the Plain” of which these are the beginning has also, like the more famous and lengthy Matthean “Sermon on the Mount,” been (mis-)read as a collection of general ethical wisdom, which is far from either Gospel writers’ intention. Attention to Luke’s narrative can help us read this present text more thoughtfully.

There is a mountain in Luke too, however. Jesus had just gone “out to the mountain to pray” and then “when day came, he called his disciples and chose twelve of them, whom he also named apostles” (v.13). This is the last of three call-stories in quick succession: Simon’s that we read last week, then the call of the tax collector Levi, now the twelve. Jesus’ descent from the mountain to “a level place,” having chosen these apostles, is rather like Moses coming down to teach the people, but here Jesus brings an entourage rather than stone tablets.

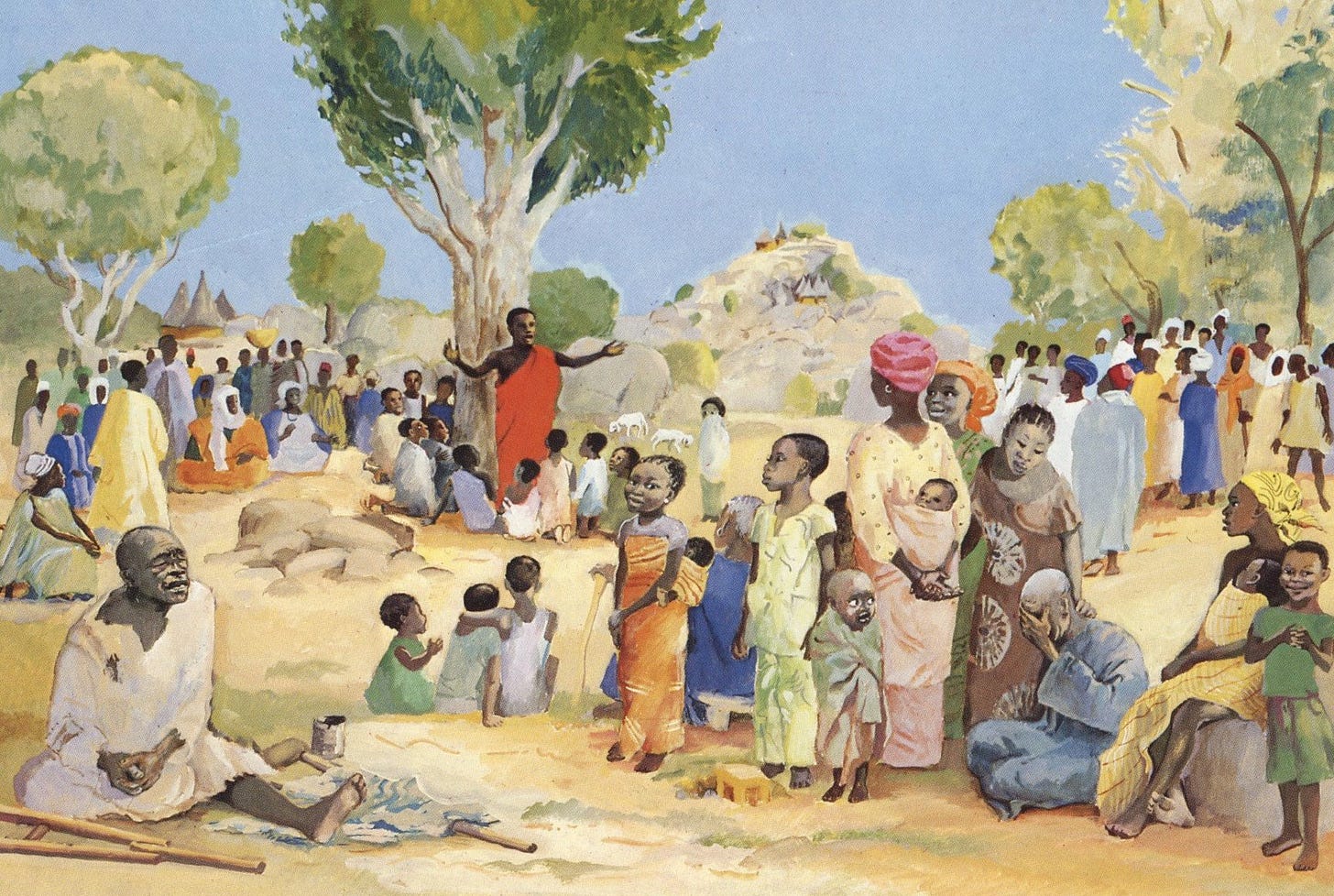

First however comes an introduction formed of deeds, not words: “They had come to hear him and to be healed of their diseases; and those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured.” This picture of the reversal of suffering and defeat of evil should be remembered in reading what follows.

Although we have already had an inaugural sermon from Jesus (4:16-21), this speech marks another sort of beginning to the ministry. In the first five chapters of Luke, Jesus has been acting alone; now the twelve and other disciples join him as he lays out and enacts a program that describes the reign of God. Where the earlier “Nazareth manifesto” focussed on the “me” upon whom the Spirit of God had come (4:8-19), now the emphasis is on a “you” that is only possible after the call of the disciples.

Three immediate differences should strike the reader in whose mind Matthew’s beatitudes may be the default version. First is the audience. There are actually three different groups present in the scene, like concentric circles. “He came down with [the apostles] and stood on a level place, with a great crowd of his disciples and a great multitude of people from all Judea, Jerusalem, and the coast of Tyre and Sidon” (v. 17). The twelve are the inner circle; when Jesus “looks up” and speaks though, it is to the intermediate group (“disciples”), not (just) the twelve. His “disciples” must be assumed to be a considerably larger (and more diverse!) group than the twelve men, whose significance by the way is probably as new “patriarchs,” like the twelve sons of Jacob, tribal heads of a renewed Israel.

He does not speak directly to the crowd who have come “to hear him and to be healed” (v. 18), but they are clearly present and listening. They are observers, rather like the reader perhaps, able to hear the message and consider whether and how it might apply to them also.

Second, these beatitudes are addressed to “you.” This contrasts not only with Matthew’s version, but also with the usual form for such statements of blessing and favor, often called “macarisms” because of the Greek word makarios (translated here “blessed”) with which each beatitude begins. These are also found in the Hebrew Bible (“Blessed is the man who walks not in the counsel of the wicked, nor stands in the way of sinners…” [Ps 1:1, RSV]”) and in the Dead Sea Scrolls (“Blessed is he who speaks with a pure heart and has no slander on his tongue” [4Q525]) and elsewhere. As in those examples, macarisms are usually in the third person, giving them a general significance. Luke’s “you” version is thus strikingly original, and has a more personal and situational tone: these are not statements about the world in general, but a call to those present to listen and consider.

Third, each of Luke’s beatitudes addresses an unmistakably concrete, literal situation. “Blessed are you who are poor” sets the tone. Then come words of hope to those who are hungry, who mourn, and who are hated and excluded. Each will receive the thing they lack, or perhaps already have; Luke Johnson points out that the “outer” pair have their situations recast, shown a different reality than what is apparent. The “inner” two are promised a future where their current situation is reversed.

There is no responsible way to read these as about anything other than what they seem to mean: material need, and reward. Of course these beatitudes do include interior dispositions, experiences of loss and exclusion, as well as economic circumstances. Yet we must hold off from reading Matthew’s version into this, not just for the sake of understanding Luke, but also to appreciate Matthew. This isn’t the “poor in spirit,” this time at least. Poor means poor. The scene where the crowd has been seeking healing and power from him emphasizes the concrete nature of the teaching.

We have already seen that the addressees are “you,” those with Jesus, not the poor of the world in general. The last of the beatitudes underlines this: “Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man” (22). The conditions of poverty, hunger, mourning, and rejection here are those that follow from discipleship. While God’s power is always against oppression, and with the poor, this is something more specific: it is the promise to the disciples that the consequences of following Jesus may seem costly, but that in reality, and in the end, God’s love wins out.

The beatitudes in Luke are also followed by a corresponding set of “woes,” with the same themes. These open up further the question of the mixed audience; there are apparently some of those listening, among the “you,” who are wealthy, well-fed, and so on. Are these disciples too? The concentric circles of the audience allow us to understand that authentic discipleship is not a status to claim, but a form of life which will have concrete expression. Not all must be poor, hungry, mourning, or reviled to authenticate their discipleship, but some who claim the title of disciple—or even apostle—will prove to be recipients of woes instead of blessings. After all, Judas the traitor has just now been named even as one of the inner circle.

Luke’s three circles of listeners allow the reader to be, like the crowd, both a bystander yet also one to whom Jesus speaks, if we choose to listen. Modern western Christians are not used to the idea that concrete disadvantage is a normal correlate of following Jesus; until recently, claims of persecution in the developed West have largely been (very) unconvincing. Perhaps this will change, however, as political forces seek to co-opt the name of Jesus to favor wealth and power against the Gospel. And it has always been true that those truly following Jesus, who have come in closer to listen—who have “left everything,” as the call stories of both Simon and Levi reported them doing—will re-learn with him what true joy and true plenty are.

Thank you for highlighting the Beatitudes which I consider at the heart of the Gospel. While I prefer the Matthew version, both versions communicate the hope of salvation and the demands of discipleship.

I always like when this word makarios comes around because every time Tim has to explain the meaning of the name of his company (Makarios Consulting), it gives him a chance to do a sly bit of evangelism. Thanks, as always, for your thoughts.