The arrival of a new liturgical year, and reading a different Gospel, seems to imply a major change of scenery or topic. Instead there is a strong sense of continuity between recent Sunday Gospels and this one. The last few weeks of each lectionary year focus on the ends of things, and so too Advent starts—paradoxically, but importantly— with the end. While Christmas lies ahead, the focus of the season is at least as much on a second coming of Christ as the first.

Mark’s Gospel, which we now begin to read for a year, is generally regarded as the first of the four to be written, and as a source for Matthew and Luke. This relationship accounts for part of the continuity. Although we did not read it, Matthew had a version of the same material that is read in today’s Gospel, just prior to the last three parables that closed the year (Matt 24). So here in Mark 13 we are still, or again, dealing with the end, even at the beginning.

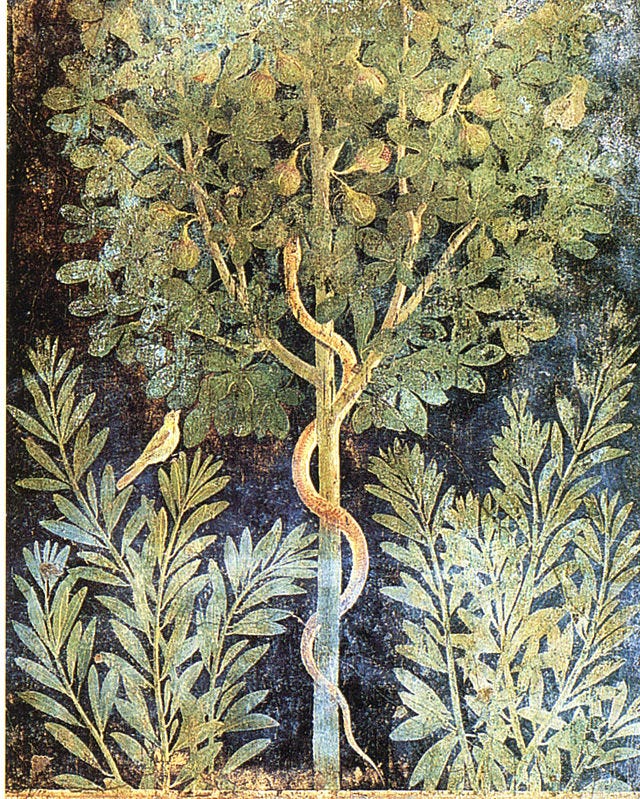

This passage combines three elements, part of an apocalyptic discourse that takes place after Jesus’ final arrival in Jerusalem. The first part of the passage is a striking depiction of the coming of the Son of Man, with whom Jesus obliquely identifies himself. Second is the lesson or parable of the fig tree. Last is a further parable that reads as a simpler version of the Talents. In Mark, this speech is distinctive not just in content but in length; it will become evident that in Mark Jesus talks less and does more, relatively speaking. In fact this passage is part of Jesus’ longest speech in the whole Gospel of Mark—there is no extended moral treatise like the Sermon on the Mount—which gives its apocalyptic flavor even more force.

The first part opens “after that suffering,” alluding to verses we did read in Mark’s apocalypse; these (vv. 1-23) address the end of Jerusalem itself and subsequent persecution of believers, as well as critical events that could apply either to the Jewish War of the late first century, close to the time of writing, or perhaps to other anticipated disasters. The editors of the lectionary give us just the aftermath or lessons from these events, and try to spare us some of their drama, with mixed results.

I imagine there are preachers—not many Anglicans thankfully—trying to make specific connections between current world events and the teaching of Jesus about the end of the world. This is unlikely to be a temptation for those reading this. It was however already a risk in Mark’s time, since there are hints here of calming enthusiasts for whom the drama and tragedy of the Jewish War was not merely a vindication of Jesus’ sayings, but supposedly guided their guesses about the end of everything. We find, just before our passage today:

And if anyone says to you at that time, “Look! Here is the Messiah!” or “Look! There he is!”—do not believe it. False messiahs and false prophets will appear and produce signs and omens, to lead astray, if possible, the elect (13:21-22)

Our risk may well be the opposite one, of failing to make the connections at all. Faced with our own historical disasters—the Gaza war most obviously, at the time of writing—we are uncomfortable with seeing God’s hand in such terrible events at all, and instead tend to focus on what these combatants really ought to do, if they were inclined to pay attention.

This is not enough, even if it is true in itself. Our hearers on Sundays need more than to be reminded of moral codes, and thus to wring their hands over the gap between the news and the demands of justice and peace. When life falls apart, in war or in more private struggles, we need to do more than offer sage advice about how things ought to be, or ought to have been. We must instead dare to help find God’s presence in the midst of whatever is taking place, however difficult this is.

The curious fig tree growing in the middle of the passage provides a clue. Mark’s Jesus actually says “from the fig tree learn the parable” although most of our translations call this a “lesson.” Jesus encourages making connections, between even natural repeated events like the appearance of new growth on the fig, and by implication with ephemeral and dramatic ones too, and the possibility of God’s action. Yet a parable points to something other than itself. While history is not the basis for predictions, it is always offered for lessons. If we are still left with the difficult implication that the figs and the fights alike bring the question of a final end to our minds, this means something other than making predictions about when. As the final parable insists, this is about readiness.

In the middle ages, Advent was associated not so much with the events of an unknown future apocalypse but with the clearer ultimate end of each person. The quattor novissima, the Four Last Things, became traditional topics for the Sunday sermons: death, judgement, heaven, and hell. Awkward as these may be in a season when people expect (or demand) comfort and joy, they remind us of the personal character as well as historic and cosmic aspect of what Advent promises or demands.

The message of the end is neither a mere calculation, nor a vague future event. It is necessarily personal as well as political, since while in one sense the end still does not seem to have arrived, it has come for every human who lived since Jesus did, not only at death but certainly then. Yet death is too late to be the moment of truth. We find this possibility of acknowledging redeeming presence, and judgement, in every lived moment in which we remain attuned to the reality of God; the fig tree and the war alike call us to be ready for the possibilities and challenges that God offers in the present moment.

History, nature, and the course of each of our lives thus hint at the need for, and nearness of, the one who is coming. This lesson of the fig tree is bound up with the sense of urgency that will accompany us through a year of Mark, not just in Advent. Jesus urges attentiveness to our own reality now, and readiness for whatever may be coming: “And what I say to you I say to all: Keep awake.”