After Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem, each of a series of local leaders and factions has taken their turn at posing questions; the lectionary skips over one from the Sadducees about the resurrection (probably because it is read in years B and C from the versions of the other two Synoptics), and now come two episodes involving Jesus interacting with the Pharisees, who were also implicated in the Gospel last week about the tax coin. This one however involves not only a question from the opposing side, but also a riposte from Jesus, where he poses his own difficult question to them. The fact that Jesus turns the conversation around signals a shift in the course of the narrative.

Just as for other sayings in this period after his messianic arrival in Jerusalem, we do well to pay attention to that context, of crisis and conflict. This first part of the reading, the question of a great commandment and the famous answer about love of God and neighbor, again risk becoming unmoored from the narrative. Of course Jesus’ words have a universal significance, but again the backdrop makes a difference.

At the time I am writing, the challenge of reading Matthew—or the New Testament generally—relative to the fraught history of Jewish-Christian relations feels unavoidable. While this has come up before, it is important—let’s say crucial—to remember there is no conflict depicted here between Jesus and Judaism, let alone between Christianity and Judaism. Jesus in this passage is being presented as a paradigmatic Jew, both as a teacher of the law more effective than his interviewer, and also as the true Son of David, the Messianic King. Matthew also is clearly Jewish in belief and practice. These are conflicts within Judaism, at this point.

The one asking the question is a “lawyer” associated with the Pharisees, but the legal expertise is what is emphasized here. As often in this Gospel, Jesus himself is depicted as a law-giver like Moses; while this perhaps had its peak moment in the Sermon on the Mount, it recurs here in a sort of equal and opposite way, the result now as pithy as the Sermon was expansive.

The question to Jesus is described as a form of “testing” (22:35), or in older translations just “tempting.” This word is always an indication of bad faith in Matthew; it is what "the tempter” does in the story early in the Gospel (4:3), and what we pray to be delivered from in the prayer Jesus teaches (6:13), as well as in similar stories of entrapment or ill-will.

The answer about the greatest commandment then is a response, not just to an abstract question, but to the ill-will manifest in the encounter. Jesus’ assertion that love of God and neighbor are the essence of the Law and the Prophets—meaning of scripture itself—constitutes a rebuke, as well as an answer. While the use of the Law of Moses as a weapon against him is something of its own time and place, we can take from this a reminder that scripture in general cannot properly be weaponized as a means of enshrining anything that is in conflict with the basic realities Jesus identifies as its core. Fundamentalism fails here most profoundly, poring over the details of revelation while ignoring its basic shape. Its shape, Jesus says, is love.

Jesus of course says this at the threshold of his paying the ultimate price of love, thus reminding us that love may nevertheless be difficult, and complex.

The other part of this Gospel is his curious counter-question about the Messiah as Son of David. This moment where he takes his interlocutor to school also continues the theme of scriptural interpretation and authority. Jesus has already implied that the questioner understood neither him nor the scriptures. His own demonstration of his expertise follows on from his identification of scripture’s real heart.

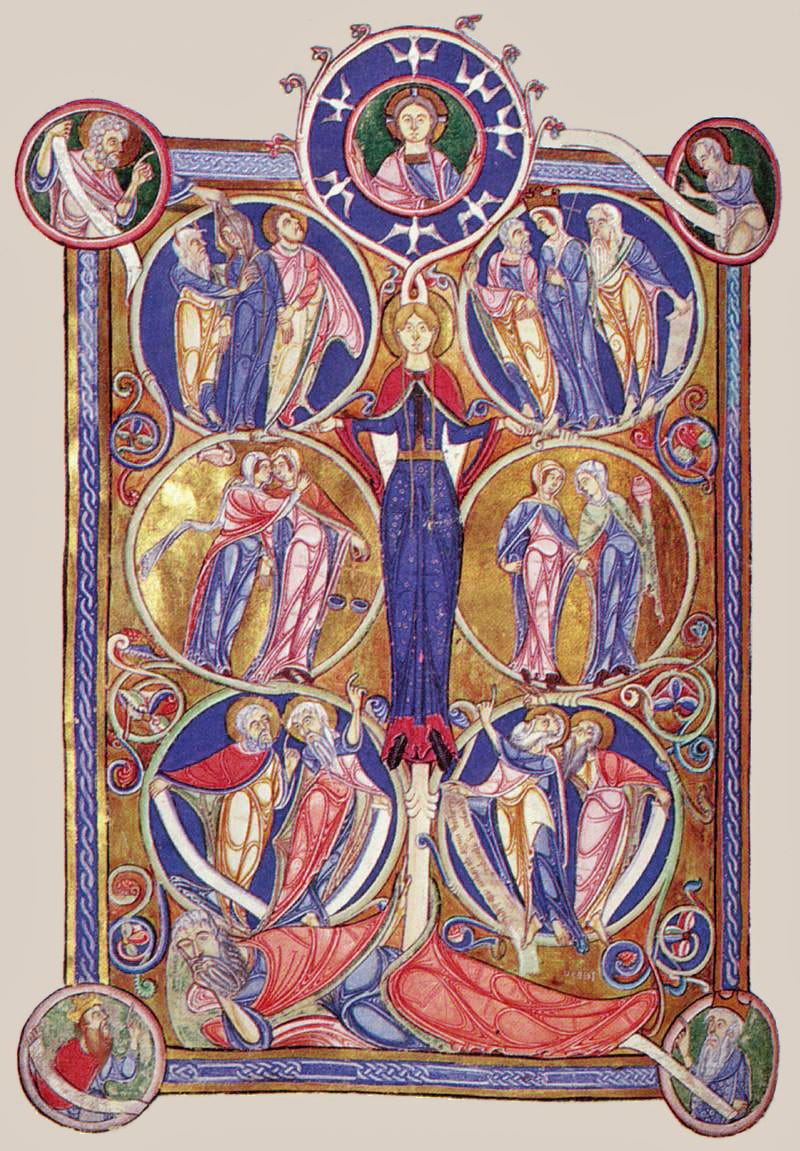

Matthew uses this title (Son of David) more than any of the other Gospels (ten of the sixteen occurrences are in Matthew). The Gospel begins with the genealogy of Jesus, “An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (1:1).

In the more immediate setting of Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem, the title has been particularly prominent. As he left Jericho to start the journey to Jerusalem two blind men call on him (twice) as “son of David” (20:30-31); then as he enters the city, the crowd calls out “Hosanna to the Son of David!” (21:9). a detail which is recalled when describing the reaction of the chief priests and scribes (21:15). Now just a little later—all this takes place just the day after the triumphal entry—Jesus raises a question about the title and its meaning. So this question is asked in the tense atmosphere of his challenge to the local and imperial authorities.

The expectation of a Davidic Messiah was well-established, but Jesus’ question implies it was not well-understood. Despite often being called Son of David, Jesus will now be acting in ways that reinterpret or even subvert standard views of messianic identity and mission. Jesus assumes one general understanding of the time, that David is the author of the Psalter as a whole, which raises some other issues of course but which is not really the point here—this shared assumption is not contested, and Jesus’ point is the nature of messianic identity, not the history of the Psalms.

By asking how the Messiah can be David’s son—even though we as readers know already that he is, and that he is Jesus—Jesus is querying the character and mission that tradition had established for the Messiah. Quoting Psalm 110, originally a Psalm praising an Israelite king whose majesty was being lauded as a kind of exaltation to God’s right hand, Jesus makes David the speaker and hence has him praise the Messiah—”my Lord”— as one greater than himself. And so too Jesus will be, even while seeming from a human point of view not to claim the forms of power that characterize kingship.

Jesus’ way of being Son of David will thus be distinctive. He will embody the two great commandments, and his love of God and neighbor will lead him to the cross rather than to a more conventional form of kingship. This, not political power as usually understood, will be the beginning of his exaltation to God’s right hand, the place where his real kingship is revealed genuinely as well as ironically, when he is publicly acclaimed “King of the Jews.”

Why is Jesus' crucifixion the ultimate price of love? When I try to answer this I start with Jesus' teaching of God's forgiveness of our sins being something of which he assures those he heals, whereas at the time it was thought to be something that was granted in response to paying for a perfect animal to be sacrificed on the altar in Jerusalem and thus under the control of the priests. Jesus was cutting into their revenue stream, it could be said. Certainly in Matthew's gospel Jesus is constantly butting heads with the religious authorities. And they are portrayed as prompting the Romans to crucify him. And we know the Romans don't need any prompting; they could have arrested and crucified Jesus if only because he was attracting large crowds at Passover which always made the Romans fear rebellions. Still, exactly how the crucifixion could have been something under Jesus' control, so that his undergoing it constituted the ultimate price of love, is something that I don't quite get. (Of course I am not a believer in penal substitutionary atonement - if I were the answer would be obvious.) I would appreciate your sharing any light on this that doesn't require a dissertation 😊.

Really helpful commentary. I have preached this multiple times but never seen its context quite so explicitly. Thank you.