The familiarity of the Parable of the Sower provides an (ironic?) example of its message—we know it, but do we understand it? Let those who have ears, listen.

Although this famous story occurs in all three Synoptic Gospels, this is the only time in the three-year lectionary cycle it comes up. The Gospel today is shared as usual with the Roman lectionary, but while readers of the RCL jump from the parable (vv. 1-9) to the explanation (18-23), the Roman Catholic reading can include the crucial intervening section about the purpose of parables (vv. 10-17) as well, whose omission in the revised lectionary baffles me (see below). This would be a very good day to just read the whole passage.

The importance of including vv. 10-17, the discussion of parables generally, is that the Sower is presented as exemplar of parables as a whole. Those verses (found, in some form, in all three Synoptic versions ) come before the third section (18-23) that offers a more specific interpretation of the Sower, but these intervening verses are at least as important to understanding the Sower as well as other parables.

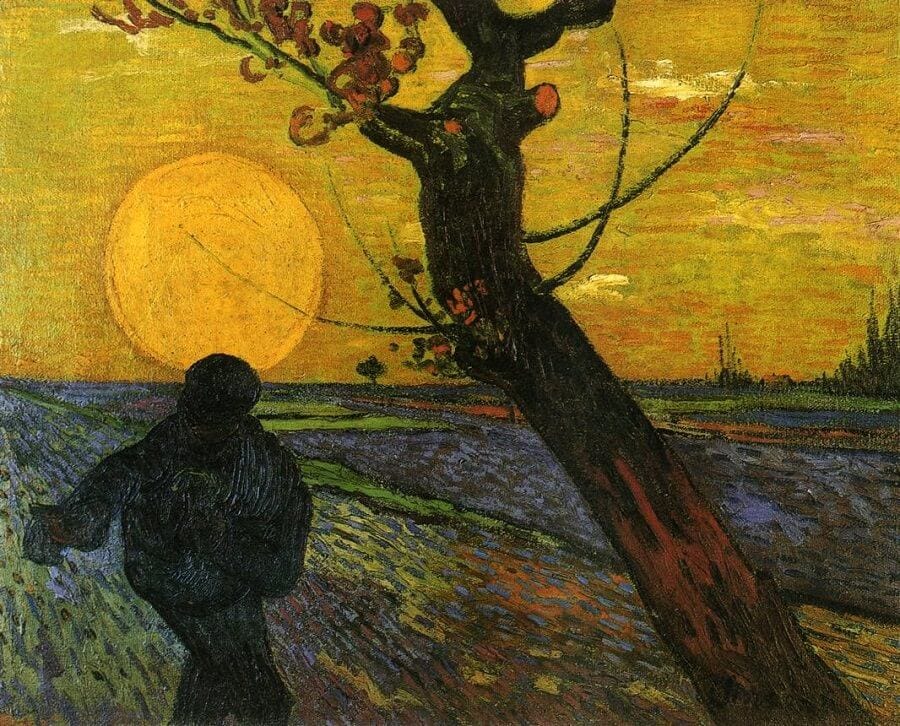

The Sower parable itself then (vv.1-9): this agricultural story involves more than just the wonders of creation or some “happy farmer” fantasy. The typical Galilean peasant who might sow a field was living under occupation, and likely in a dependent economic relationship like tenancy or day-laboring. The obstacles to plenty were not just the marginal state of the land being sown as described here, and hence the uncertain returns, but poverty and indebtedness regardless of a decent crop.

The key thing about the parable then becomes not just the diversity of soils—not really so curious perhaps, in the real occupied and economically stratified Galilee itself—but the end, the miraculous yield of what fell on good soil, and how that yield outweighs the frustration and struggle the peasantry would associate with the poor soils. To yield “hundredfold, some sixty, some thirty” is not usual. Much lower yields would be expected (especially with the poor state of this parabolic field), but this suggests a paradise in which all needs are met and where the despair associated with the weeds, the stony ground, and the other apparent failures is swept away. In God’s reign the poor who sow— the little ones who are God’s favored (cf. Matt 11:25)—will have enough.

Is this clear? It can be tempting to think of all this as Jesus the earthy communicator with the common touch, explaining truths in simple terms using familiar images from rural life. An immediate problem for this attractive folksy explanation arises when—in all three Synoptic versions—the disciples, having heard the Sower, immediately ask Jesus what it meant. Here in Matthew’s version they even ask why he speaks in parables at all. No, parables are not clear.

The problem for the salt-of-the-earth understanding deepens when (again in all three versions), Jesus explains parables as a means of incomprehension: “And he answered them, ‘To you it has been given to know the secrets (mysteria) of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given’” (v. 11). Matthew expands the Mark version with a fuller quote from Isaiah 6 (this is from the famous vision scene of the prophet’s call; it makes for an interesting contrast with the Isa 55 reading, for those using Track 2): “You will indeed listen, but never understand, and you will indeed look, but never perceive. For this people’s heart has grown dull, and their ears are hard of hearing, and they have shut their eyes…” (vv. 14-15; from Isaiah 6:10 in the Septuagint).

So parables in general perform something like what is described in this particular parable: offering, creating, transforming, sometimes disclosing but just as often (more often?) falling on the stony ground of ears that do not want to hear. And yet we may have preachers offering the passage as something like the direct opposite of how the Gospels do: Jesus the gifted anecdotalist, how the wonder of nature brings growth, etc.

The nuance of Jesus’ startling answer does shift a bit between the three Gospel versions; in Mark, presumably the oldest, the question and answer (“And he said to them, ‘Do you not understand this parable? How then will you understand all the parables?’” Mark 4:13) reflect the usual picture in that first Gospel of the disciples as generally hopeless, not so much dim-witted as incapable (like all of us) of grasping a messianic identity that only the Cross could reveal. In Matthew however, the disciples generally get a better rap, and this is true here: Matthew actually gives them a beatitude instead of a rebuke: “But blessed are your eyes, for they see, and your ears, for they hear” (13:16) While Luke also knows this saying, he places it elsewhere, and Matthew’s addition of “ears…hear” is obviously a link with v.9. So the meaning of the parables for Matthew is not completely obscure, but remains a “mystery” (v.11 - this is the only time mysterion appears in the Gospels, and “secrets” in NRSV is surely rather flat), revealed to some, and not others.

The difference between hearing and not hearing recalls differences referred to in last week’s Gospel (“you have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants” 11:25). This is not merely a paradox, or some arbitrary distinction between those chosen to hear and those not; the genre of parable allows those unwilling to hear, not to hear. For Matthew the point is not so much privilege for the disciples, nor the obscurity of the parables, but the challenge to the reader (as a disciple) that they have been included in the mystery, where others have not.

The blessing of having ears that hear is not a prize, it is a way of being. This is not meant to promote in-group thought, let alone smugness; rather it fits with the picture of Jesus’ mixed reception in the previous chapters (and otherwise). The disciple understands (then and now) that the indifference and hostility of the world to what is just and true (“Alternative facts,” anyone?), and hence to Jesus and the Gospel, is not only of long standing, but can even play some part in God’s purpose, as the quote from Isaiah suggests.

The third section, the explanation of the parable (regarded by many scholars as of separate origin), with its allegorizing tendencies (correlating all sorts of details with personal experiences of faith and failure) reflects less the Galilean peasantry I suspect how the later audience of the Gospels experienced their own struggles of ongoing opposition and failure. This is not however an invitation to leave behind the setting of Jesus’ ministry, and merely correlate these “soils” of early Christian experience with our own biographies. Rather these details of interpretation amount to a later (and differently contextualized) picture of how the “Word of the Kingdom” (v. 19—a unique phrase to Matthew) continues to prevail over the varied failures of human response in different settings, and over varied forms of injustice and want. The parable was offered to people who experienced food insecurity, and their experience should not be erased in favor of musings about wavering belief and shallow commitment—even though these do matter too.

The point then is not just that some people hear and respond and others do not, let alone pondering just who in our experience does and why; it is that the power of the “Word of the Kingdom” is offered to God’s chosen, the little ones, and that this power redeems the whole field, which is the world. Let those who have ears, hear.

Another pithy and useful reflection, cast on fertile ground, let us pray.

How often do preachers read this passage and wonder whether their stories are being cast on what sorts of soil...

A plea (or polite request) for fewer parenthetical asides. While some are for citations, I counted 27 (not including em-dashes - are they equivalent?) in this entry.