Transfigurations and Multiplications

Feast of the Transfiguration (Episcopal and other), Luke 9:28-32; or Pentecost/18th Sunday in Ordinary Time/Proper 13, Matt 14:13-21

Depending on where you are in the world and in the Church, you may have one of two quite different sets of readings for this Sunday, August 6th. For The Episcopal Church in the USA and many others, it’s the Feast of the Transfiguration. In some other places and especially beyond the Anglican Communion, it’s the Tenth Sunday after Pentecost/18th Sunday in Ordinary Time/Proper 13 (those last three are all the same thing).

In liturgical traditions where Saints’ days and related feasts are observed, the most important of these (often called “Red Letter Days,” because of how they were printed in color in old books) have their own readings used when they fall on a Sunday. So some of you are reading Luke’s account of the Transfiguration for that feast day.*

The Revised Common Lectionary however also has the Transfiguration story on the Sunday before Lent (in the older version of the three-year lectionary used by the Roman Catholic Church it is read on the Second Sunday in Lent). The Sundays between Epiphany and Lent have themes that relate to Epiphany, and so the Transfiguration story is offered as a moment of divine disclosure that precedes Jesus’ fateful journey to Jerusalem. Some people with authority have taken this to mean that pre-Lent Sunday had itself become a “feast of the Transfiguration.” That’s a mistake but in some places it’s become the rule (yes, sometimes liturgical change does work this way). In these cases, and in Churches in which Transfiguration is not a feast anyway, the regular cycle of reading through Matthew is preferred or allowed this week.

I have already commented on the Transfiguration story this year when it was read before Lent, but there I encouraged preachers to consider the specifics of Matthew’s version that was set that day, whereas Episcopalians keeping the feast this week read Luke. So in what follows I offer comment first on Luke’s Transfiguration, and then touch on Matt 14:13-21 as well.

Luke’s is the fullest account of the Transfiguration and has some distinctive features. One is the emphasis on the conversation between Jesus and the two glorified prophetic figures. Here in Luke, and only here, we are even told its subject:

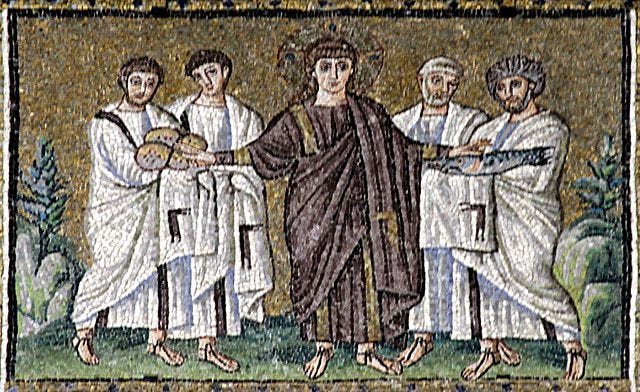

…Moses and Elijah, talking to him. They appeared in glory and were speaking of his departure, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem.

This “departure”—in Greek exodos—is a striking way of describing the work of the coming events in Jerusalem, which are not just Jesus’ “exit” but like the first Exodus will be another moment of God’s liberating presence in history, echoing that in which Moses led the people to freedom.

Calling these coming events an “Exodus” affects how we understand both liberation and Passion. The conversation thus becomes not merely a sign of Jesus’ glory, but of its specific character and its requirements. He will free his people gloriously, but as for Moses and Elijah this will come at a price.

This focus on the coming Passion continues in Luke’s narrative. The sleepiness of the disciples, unique to his version of this story, reminds us of another occasion they were unable to stay awake with Jesus, in the garden (see Luke 22:45-6). There is also a distinctive emphasis here, as there, on Jesus’ solitude; the exchange with Peter takes place while the exalted ones are leaving Jesus (v.33) and then Luke alone notes that “When the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone.” The events to which the conversation among the glorious ones referred, where Jesus will face his fate by himself, is being anticipated.

In discussing the parables recently I emphasized reading Matthew, and the Gospels generally, with attention to ancient economic realities including food insecurity. The feeding of the five thousand is one of the most obvious stories that assumes the relevance of hunger. For later readers in more privileged settings, the spectacular nature of the miracle may distract us from the fact that it was loaves and fishes that were multiplied, and many hungry people fed.

Jesus’ desire and capacity to feed the people are closely linked. None of his miracles or signs reflect mere power over nature or matter, but illustrate and make effective his care for his people. The centrality of food to the experience of these early hearers and readers is evident through the Gospels. The images of the parables in chapter 13 all suggested it. The presence of the petition “give us today our daily bread” in Jesus’ prayer should be taken at face value, even if that is not all it means.

This story also echoes the eucharistic practice, grounded in the Last Supper stories, which the first readers of Matthew knew and celebrated. Jesus “looked up to heaven, and blessed and broke the loaves, and gave them…” (14:19). The character of early Christian community as sort of community feeding program is evident too (read Acts 2).

We even have a possible early reaction to this centrality of bread and feeding in John’s Gospel, where after the parallel story of feeding the crowd (see John 6) Jesus criticizes those following him just because they “had their fill of the loaves.” The validity of this complaint depends on context. We need more than bread, but we do need bread. It is not enough for us just to feed and be fed physically; but if these things are ignored in a world where hunger and poverty persist so scandalously, we are scarcely fulfilling the Gospel.

The role of the disciples in the story is shaped differently by Matthew, in a way that fits the narrative of this Gospel and the continuing development of their ministry. Recall that the parables discourse (Matt 13) was not really about seeds and fish, but about the power of the Reign of God, and the distinctions it makes among those who hear and don’t. The structure of the chapter showed the disciples were being educated and equipped, distinguishing themselves from those who had ears but did not hear. So they gave Jesus their “yes” when he examined them at the end of that discourse.

In Mark’s earlier version of the feeding story, the disciples—always a dim bunch in Mark—get into passive-aggressive territory when Jesus tells them to get involved in feeding the crowd, asking “Shall we go and buy two hundred denarii worth of bread, and give it to them to eat?” (Mark 6:37b). This comment disappears in Matthew however; they are now willing, but lack the ability or confidence, saying only that their resources are limited (“We have only five loaves here and two fish”). I cut off the quote above of the Last-Supper-like formula in this story with which Jesus takes the loaves, but it actually emphasizes their role; he “gave them to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds. And all ate and were filled” (vv.19-20).

The disciples themselves have become the means by which this miracle takes place, just as clearly as when Jesus sends them earlier (chapter 10) to extend his mission. This story then functions as a model and a challenge to offer the bread of Jesus, literal and figurative, sacramental and substantial. Despite their lack of understanding, the disciples are able to share in his ministry. The test is not their sophistication or even the depth of their faith, but their willingness to accept the broken bread he gives and share it; we are offered the same opportunity.

*The Australian situation is further complicated by the Mark version being set for the August Transfiguration feast. I haven’t felt able to include that as well, with apologies.