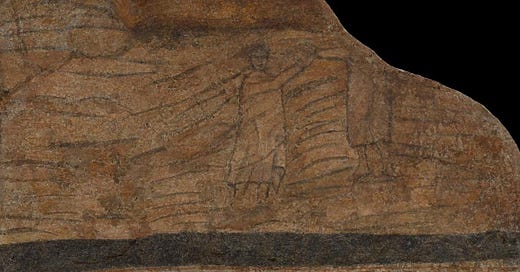

The scene of Peter walking to Jesus falteringly on water has become so much a part of this story of Jesus, the disciples, and a storm, that it is hard to imagine it otherwise; what could be the oldest surviving images of Jesus include a depiction of this very moment (see below). Yet the earlier version in Mark (6:45-52) had not included Peter’s uncertain aquatic journey (Luke does not include the storm scene at all, nor any story equivalent to the contents of Mark 6:45-8:26 despite, like Matthew, using most of Mark). So again we need to grasp Matthew’s intentions when considering this text.

Last week and this, the narrative of Matthew offers stories of Jesus’ power whose remarkable character is intended to teach, as much or more than to astound. In our setting, where some forms of scepticism hold sway (although people also seem willing to believe anything), the mere fact of multiplying loaves or walking on water risks being too startling—or entertaining— for us to get past the spectacle to the heart of the matter.

In Jesus’ time the idea of walking on water was seen as a divine power, but the desire to or pretense of doing so was also a symbol of human arrogance and of tyranny. The Second Book of the Maccabees, written not long before Jesus’ time, scorns the tyrant Antiochus IV Epiphanes, defiler of the Jerusalem Temple, who thought “in his arrogance that he could sail on the land and walk on the sea” (2 Macc 5:21). The even more notorious Caligula had a temporary bridge built across the Bay of Naples, 50 km long, to enable him to cross on foot— since it was more appropriate for a god (him) to go over water this way rather than wallowing in a boat.

So the scene where Jesus walks on water was likely to remind ancient readers both of the prerogatives of divine power, and of well-known examples of human presumption. On the first, the sense of divinity revealed in this action is encouraged by Jesus’ response “It is I.” While this phrase could be just straightforward self-identification, it is the same as the “I am” that appears often in the Hebrew scriptures, and in John’s Gospel, as a divine self-announcement. When the disciples recognize him (v. 33) as “Son of God” this doesn’t come from nowhere.

The Jesus who walks on water is not only a divine being, but a more legitimate ruler for Israel, by contrast with Antiochus or Caligula. Matthew makes these connections more clearly than we have seen; in our tour through the Gospel, even those who read the multiplication of the loaves last week had jumped over the story of Herod Antipas (son of the other Herod, so prominent in Matthew’s nativity) and the death of John the Baptist (14:1-11). So when Jesus immediately after that story of violence multiplies the loaves and then walks on water, Matthew presents him as a legitimate, effective, and compassionate ruler for Israel, in contrast to the oppressive conduct of the Herods.

The walking on water story is thus Jesus undertaking the royal procession of the true Messiah, whose rule promises plenty and freedom in place of the familiar exploitation and war. The stilling of the waves represents not merely power over nature, but a care for his people.

While Matthew may be giving some special attention to Peter, given the apostle’s subsequent role in the earliest Christian movement, it is important to remember Matthew’s presentation of the disciples generally. We have seen in recent Sunday Gospels how the group are presented as growing in faith and understanding. The growth is of course distinctly non-linear—there is no arc tending clearly to wisdom or strength, and crises a-plenty still to come— but a growing focus on the need for them to follow, trust, and participate in what Jesus is doing. While the Gospel is about Jesus and the reign of God, the disciples are the key audience to the Gospel within the narrative itself, modeling how we might respond as much as how they did. Despite the most monumental failure still to come (26:56), they will ultimately receive the task of Jesus’ mission.

Peter here becomes for the first time a sort of representative disciple, providing what is needed when the reader might be asking “what do I do?” This is also evident in the Transfiguration story some of us just read again recently. The parallels are intriguing: Jesus’ divine glory is revealed at night in an astounding way, and Peter responds despite fear, even though his response is not ideal. Peter’s character is emerging as a personal embodiment of what the disciples have been learning in these events, parables, etc., bumbling as he may be. The Lectionary and the narrative are out of step, though; Peter has not really appeared in the familiar way before, since the Transfiguration in Matthew will not take place until chapter 18, and so this story is more like a preview of that glory, and of that imperfect but necessary response.

At the end the disciples “worshipped him” (v.33). This term is surprisingly difficult to grasp, because our uses of “worship” are, frankly, often insipid and misleading. Mainline Christians in the USA and elsewhere have used “worship” for their traditional liturgies, which is fine so long as we understand that “worship” doesn’t mean liturgy, it means devotion and obedience. Sacramental worship, the Eucharist, has a particular claim to being “worship” because we do this in obedience to him. Otherwise liturgy is symbolic and communal center of worship, not its full extent. Economics and ethics and relationships are as relevant to worship as is liturgy.

Our failure to understand or express this however is reflected in tendencies to redefine “worship” a further step away from obedience and service, so that it increasingly gets identified with creative arts in mainline Churches, while evangelicals translate it without embarrassment just as contemporary Christian music.

In the boat however, the disciples are not curating or performing, they are prostrating themselves (prosekunēsan), which is the literal meaning here. Flat on their faces, they are embodying their dim but growing understanding of this mysterious one; and their joy as well as their apprehension anticipates their future as genuine “worship leaders,” people who will serve him in building community, proclaiming the reign of God, and suffering for his sake, and for the sake of the world he came to rule and save.

Thank you for this reminder of the fuller, more truthful meaning of worship - particularly the obedience part. This summer I am preaching through Romans, and this week's passage with the phrase "the word is very near you" resonates with me in connection to Jesus' presence with Peter and the "It is I" statement.