The Revised Common Lectionary framers have chosen to present the Transfiguration as the culmination of “epiphanic” themes on the last Sunday before Lent. This year that means jumping rather abruptly ahead from Luke’s Sermon on the Plain, and past other parts of the Galilean ministry, and possibly at the cost of the relationship of this story with its own narrative context.

The accounts in the three Synoptic Gospels are similar in details—the mountain, the night, the glory, Moses and Elijah, the three disciples—and also in their place in the story. In all cases the Transfiguration follows the first of Jesus’ predictions of the Passion, as well as his radical call to discipleship as taking up the cross-bar of institutional violence. In Luke however more than for the others, it sits in a section where the question of Jesus’ identity is being raised, first by Herod Antipas (9:7-9) and then by Jesus himself (9:18f.). This story is a partial answer to that question, and while it does constitute a sort of epiphany or theophany, it also illustrates and interprets the divine reality in a way that stays connected with the statements Jesus has made about his identity and fate.

While the jump in the lectionary risks concealing that connection, Luke’s version of the Transfiguration does includes hints about, or parallels with, Jesus’ Passion that distinguish it from the other versions. The initial instance of such could be erased by the micro-editing of the lectionary, as found in online RCL texts and probably in printed Gospel books too; verse 28 does not actually begin “Jesus took with him Peter” etc., but “Now about eight days after these sayings, Jesus took…” Mark’s version had “six days.” So is Luke just counting differently, or inconsequentially?

This is the only place prior to the Passion story that such a temporal marker is included by Luke at all. Commentators acknowledge it is possible—not certain—that this is an early instance of the number “eight,” and especially eight days, pointing to something like a new creation or resurrection, the new day following the week as known in human history.1 Numerous early Christian authors take up this symbolism, and while here it remains a stretch, we have no better reason to explain the change from Mark.

Another distinctive feature in Luke is the emphasis on prayer at the event, unique to this version but also characteristic of this Gospel as a whole. Luke makes clear the purpose of the trip up the mountain was not the transfiguration in itself. Jesus took the three up “to pray” and “was praying” as the mystery took place. Some will remember his prayer was also a Lukan feature of the baptism story (3:21). There is in fact a good handful of times when Jesus prays before or during significant events in Luke (5:16, 6:12, 9:18, 11:1). In narrative terms, these are not so much indications that Jesus had a exemplary prayer life as reminders of his relationship to God. They also amount to glances ahead to the scene of prayer in Gethsemane, where the intimacy with God that pervades his life comes to a head (22:40-46).

Most striking of all the unique elements in the Lukan account is the conversation between the three figures. Only Luke mentions the topic of the conversation between Jesus and the two Israelite and scriptural predecessors. It is his “departure,” as English versions put it rather prosaically, but the word is more evocative in the original: it is his exodos. The “departure, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem” could be the death of Jesus, although given Luke’s unique emphasis on the ascension story it would be better to think of the whole passion and resurrection sequence as the new “exodus,” with his return to the Father as its climax. Luke suggests that these events will be an act of liberation comparable to the one Moses oversaw, so that like his predecessor and conversation partner Jesus will set his people free.

Some other features in Luke are distinctive too: Luke does not actually use Mark’s “transfiguration” language (Mark 9:2) but says Jesus’ appearance was “other”; his garments become “dazzling white,” which suggests divine splendor (see Ezek 1). The disciples also see his “glory.” This involves another nod at the passion story (unique to this Gospel, again), in the companions being not-quite-asleep, which seems to anticipate again that story of another fateful night, fervent prayer, and drowsy disciples, in Gethsemane. It is in that sleepy state, after the conversation of the three great ones, they saw the “glory” of Jesus. Dorothy Lee observes “in Luke [glory] symbolizes the celestial abode to which the mountain gives access, and also the divine presence that embraces Jesus.”2

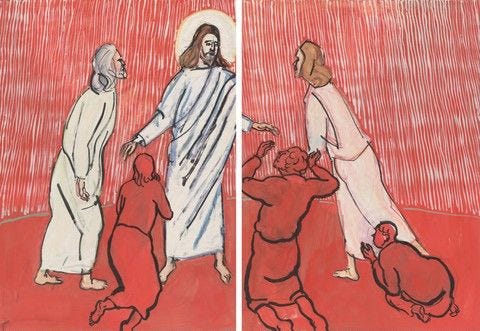

What then does the Transfiguration reveal or achieve? François Bovon imagines some readers thinking that “the doctrine of the incarnation of Jesus seems to be threatened by the account,” but points out that “Jesus is not taking on an alien nature provisionally, but rather uncovering his true identity.”3

While of course this view of Jesus is not a Christology like that of Nicea, it is also not a picture of someone whose teaching and personality just set him apart in whatever way, and onto which someone later imposed divine identity. The idea still often put about that in (say) Luke or Mark we are dealing with the story of some insightful and brave person, turned only by unrelated doctrinal developments into the second person of the Trinity, is determined not by reading scripture itself but by Enlightenment assumptions. There is no memory, even in these earliest Gospel accounts, of a Jesus without a unique relationship with God, and whose mysterious authority constantly invokes a kind of awe, and which leads the onlookers or participants in his story to acknowledge, however unsystematically, they are somehow encountering God in him.

Yet it is not that a mask has slipped. Jesus has been changed in a way that anticipates something to come, or still unfolding. Luke and the other synoptic authors do present a human Jesus, but one whose relationship to divinity is always real, mysterious and unique—in keeping with nature of the divinity manifested in the stories of Israel, represented here by Elijah and Moses.

So it is not that Jesus’ more regular daily appearance had been a ruse that cloaked divine identity. The Transfiguration story indicates that Jesus’ relation to the divine is greater and closer than even the three sleepy onlookers have suspected previously. The coming exodos is the key to this puzzle. The disciples see his “glory,” and while they do not yet comprehend it, the nature of and purpose of glory are shown here to be something other than expected.

Above all the story indicates what that divinity constitutes of which Jesus’ life makes him the mysterious representative. The God working in him is the liberator, who works in and with the poor, like the enslaved Israelites whom Moses led and the imperiled faithful whom Elijah supported. The glory this God offers is in keeping with the experiences of those two ancient ones, whose faithful witness was performed in the course of struggle. While they too saw divine glory, their recompense was not power or wealth or security, but vulnerability at least in the world’s eyes. So also Jesus’ “departure”—his exodos—will free his people from oppression, but will be manifest as surely in his taking up the cross as in the brightness of his raiment on the mountain.

Early (apocryphal) instances where this interest in eight might be paralleled are Jubilees 32 (contested), 2 Enoch 33 (date uncertain) and Barnabas 15.

Lee, Dorothy. Transfiguration. London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2005, p. 73.

Luke 1: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 1:1 - 9:50. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2002, p. 373