You may not have realized it because of the actual verses read (or not), but the brief foray into Mark’s parables last week was taking place in a boat. This chapter begins:

Again he began to teach beside the lake. Such a very large crowd gathered around him that he got into a boat on the lake and sat there, while the whole crowd was beside the lake on the land. He began to teach them many things in parables… (4:1-2)

So this is where the various parables of the seeds were set. It is not quite clear how we are meant to understand the movements in between, when Jesus speaks to the disciples privately to explain the parables, then again to the crowd, but as this week’s Gospel opens the boat is still, or again, the center of action.

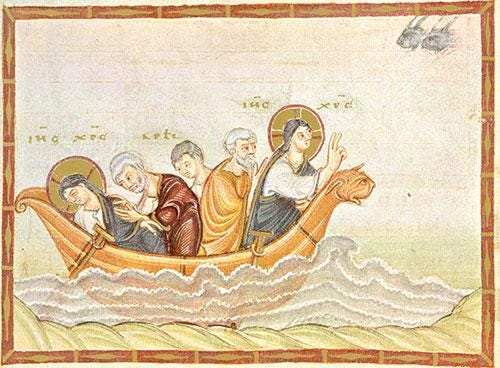

Through this section of the Gospel we find repetitions of patterns and stories, including what Elizabeth Malbon has called “echoes and foreshadowings.”1 The most obvious patterns are the two storm stories (of which this is the first) and the two miraculous feedings, which are still to come, each of which has a set of healing miracles in between. Yet even the placement of Jesus in the boat at the outset of the parables discourse hints at something that this story of the storm develops more dramatically. In the verse immediately before we start to read this week, we are reminded that “he did not speak to them except in parables, but he explained everything in private to his disciples.” The boat makes this separation real in spatial terms, and allows a physical performance of the distance Jesus places between himself and the crowds by the very fact of speaking in parables.

The boat now seems to represent the circle of Jesus and the disciples over against the crowd or the wider world. The “sea” (which is how Mark refers to the lake) itself has been connected with Jesus’ disciples since the story of their call in chapter 1. This episode with them all together in the boat foregrounds that relationship, as well as Jesus’ power relative to the elements.

Geography and topography are important in Mark. Galilee and Jerusalem, or the countryside and the city, are coded relative to Jesus’ program, his followers, and his opponents. So too the sea and the land seem to be an opposed pair; the move, first to the boat, and then across the sea, are not just distancing mechanisms, but forms of transition. Jesus and the disciples are not merely going for a sail, but undertaking a journey into places unfamiliar.

While the story as we read it in isolation cannot make this clear, the journey seems to be a transition between two worlds. The crowd listening to parables were part of the world of Galilean peasantry, oppressed but nevertheless ordered and familiar, and not least Jewish. All this was a kind of “here”; this journey is to “there,” not just to the storm but past it into gentile territory, crossing to the country of the Gerasenes. You may remember (even though we won’t read it this year) how this unfolds; demons and pigs and all populating a wild and alien place which seems to connect with the wild state of the sea. The sea itself and the storm are not just natural phenomena, but a place of risk and uncertainty.

The relationship in the boat however seems to be a difficult one, as difficult as the curious distance that Jesus had placed between himself and the crowds in the parables discourse. Just as then, the response of his (smaller) audience as a storm rises is not ready acceptance of the message, but incomprehension (or worse). And just as then, the relationship between word and deed is not what the reader (identifying with the disciples) seems likely to expect or want either.

The storm comes, and the disciples are confronted not only by fear but by a sense of distance from Jesus. While all the Synoptic Gospels contain a version of this story, only Mark has them actually reproach him as he sleeps in the stern: “Teacher, do you not care that we are perishing?” Despite their call and privileged relationship (such as having the parables explained privately), the disciples now feel not just unsafe but alienated from him; but this is ultimately because they do not really grasp Jesus’ identity or the purpose of his mission either.

This theme of incomprehension will continue through the following chapters of Mark, but it reaches an initial high point here—not so much with the storm but with its calming. Jesus demonstrates a kind of power over the world he inhabits that is different from what has been seen so far. Following on from his authoritative interactions with false leaders and his bouts with demons, now we see nature itself acknowledge his power.

Just as in the first few chapters of the Gospel, it is Jesus’ works that attest to his call and his identity, rather than words. Or we could say that the words “Peace, be still!” are the powerful teaching here. Despite wishful thinking, the words are not addressed to the disciples, nor are they readily translated into a sort of spiritual wisdom about peace and calm, at least not directly. Jesus does not soothe the wind, he “rebukes” it, with the same language used to rebuke the first demon he encountered and cast out (1:25). It is the disordered force of nature itself to which Jesus speaks, and the world obeys him.

Thus the calming of the storm is comparable to the ways Jesus has already shown divine power in confronting pain and spiritual oppression, and has shown his resolve in the face of corrupt political and religious power. All these for Mark constitute a whole, and so too Jesus’ confronting but necessary response to the disordered world (under the power of the “strong man” of last week’s Gospel) which he has come to liberate is of a piece.

The good news is that Jesus leaves no aspect of life untended in his mission to heal and save. The less good news, at least as it may appear to us as to the disciples, is that he does not act in the ways, or at the times, that suit our preconceptions about how liberation is supposed to work. To be in the boat with him really is the place the disciples need to be, but it does not feel like it. If the “peace, be still” command could be understood to extend not just to the winds but to them and to us (as indeed to the demons, and to the forces of oppression) it is still a rebuke; a command to set aside the disordered assumptions that we bring to understanding him (“Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?”) and to ponder in awe, and not just in gratitude or relief, “Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?”

Malbon, Elizabeth Struthers. “Echoes and Foreshadowings in Mark 4-8: Reading and Rereading.” Journal of Biblical Literature 112, no. 2 (1993): 211–30.

Another way to connect the reception/response of parables and storm stilling is to observe that the verb “akouo,” which, in an imperative form, prefaces Jesus’ telling of parables in Mark 4, is echoed and reinterpreted by the narrator’s commentary on the storm stilling: “Even the wind and sea _obey_ (hypakouo) him..”

Andrew, when you get to it can you please write about the enigmatic conversation on the boat following the second feeding miracle and the multiple Q and non-A between Jesus and the disciples. Thanks for the Version