The beatitudes and woes—read last week—began with Jesus looking “at his disciples,” and addressing them in particular as “you.” As this second section of the Sermon on the Plain begins, Jesus has not moved, nor have the crowds, but he adjusts subtly: “I say to you that listen...” This shift emphasizes that the reader is a part of this audience, and that what matters is not status, or location, but willingness to listen.

While the beatitudes and woes spoke of a reality that appears (or will appear) when we attend to God’s perspective, any actions implied there were God’s, not ours. Now however we enter the realm of ethics much more directly. These commands reflect the same world-view, but are framed to guide those who understand the reality of God’s reign. The distinctive way of being and knowing depicted in the beatitudes now leads to distinctive practice.

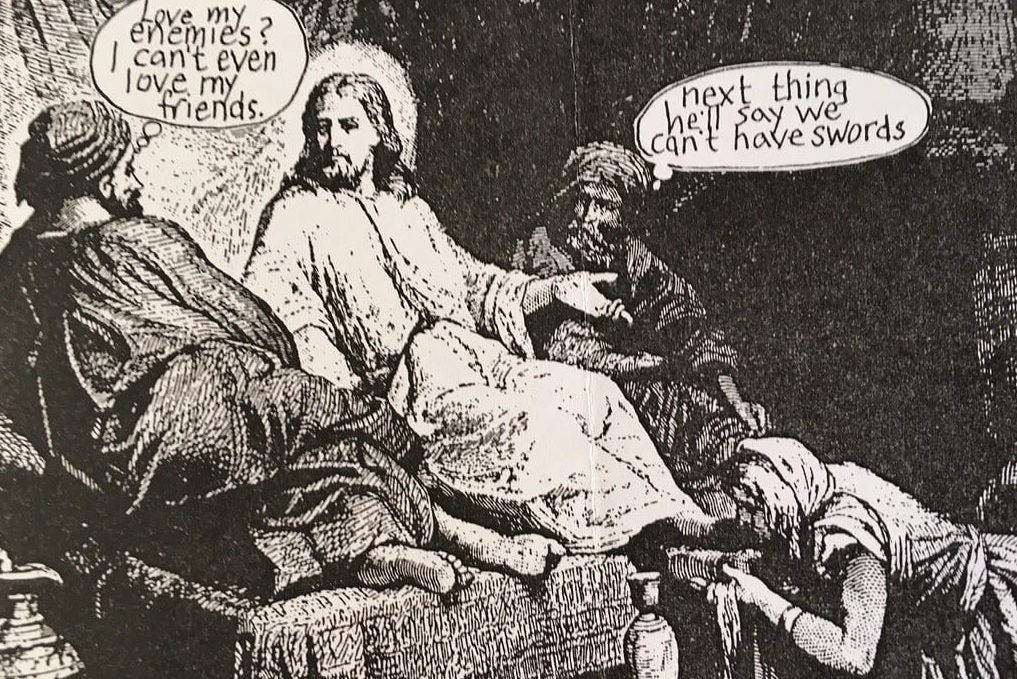

This reading moves through types of statements. The opening fourfold set of principles—“Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you”—provides the basic program. The second through fourth are expansions of the first: love your enemies. Then come four more concrete cases, and the requisite response in each: being struck, having clothing taken (whether as subject of wrongdoing or charitably is not specified), giving to others, and then a version of the “golden rule”: “Do to others as you would have them do to you.” Just as the first list started with a general principle (“love your enemies”) that expanded into the concrete commands, the second list moves from specific cases to a catch-all—the golden rule—that sums up.

While this golden rule in one form or another appears in numerous places in Jewish and Greek wisdom (and beyond), its use here is distinctive. Jesus is not its author, and so its presentation as such is no major step beyond either Judaism or Greek philosophy, which already offer the same basic insight. Jesus’ near-contemporary Hillel, for instance, is also reported as saying “That which is hateful to you do not do to another; that is the entire Torah, and the rest is its interpretation” (b. Shabbat 31a). Jesus’ originality however lies not in proposing the golden rule, but in re-interpreting it as the love of enemies, and as characteristic of discipleship.

Where typically this “do unto others” principle is seen as a summary of decent behavior, Jesus pushes much harder. Making the golden rule a punchline for those cases of non-violent and self-giving love already showed how the principles must work; the next verses (vv. 32-35) reinforce Jesus’ claim by a third set of statements, counter-examples that might otherwise have seemed to be just what the rule entails, but which Jesus demolishes. It is not enough to be kind to those from whom you expect kindness, or to whom you otherwise owe it. It is love of enemies, not friends, that marks the follower of Jesus.

At the time of writing there has been an unusual amount of public attention given the nature of Christian love because of an attempt to use theological ethics to defend deportation of undocumented immigrants. US Vice-President J. D. Vance tried to claim that the Christian ordo amoris—”order” or structure of love—means that you love “your family and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens”—exactly the sort of situation Jesus dismisses here— and that this somehow means treatment of immigrants is less important. The response from Pope Francis in the form of a letter to US bishops is worth reading.

The grain of truth (which most heresies contain) in Vance’s account is that we are indeed called to act with particular care and love towards those in our daily lives, not least those to whom we are bound in family structures, but (here’s the rub) also in whatever concrete situations of need we encounter closer than on FOX News. Love is certainly not just to “love” people in principle, at whatever distance. Yet this “ordo” of love that Augustine of Hippo named, and Thomas Aquinas elucidated, is not a theological rationale for familial or national chauvinism. Thomas in fact wrote “one ought, for instance, to succor a stranger, in extreme necessity, rather than one's own father, if he is not in such urgent need.”1

There is indeed an ordo amoris, and unless rightly “ordered,” love is not really love as Jesus means it. And the right ordering of love begins with the love of God. All this would apply even to the traditional renderings of the golden rule: we should treat migrants and refugees as we would want to be treated ourselves. The other great principle of Israelite religion, to love one’s neighbor as oneself, leads in the same direction. Yet in Jesus’ sermon we have something more radical and difficult than the common decency lacking so often now in the public sphere: love of enemies, not just of either family or of the needy, is the command.

The passage continues with the reassertion that love of enemies is the mark of the follower of Jesus, and then promises rewards that again echo the divine order conjured by the beatitudes. The rewards are great, because to be merciful is to imitate the nature of God (v. 36).

The reward to the one who can love as Jesus calls us to is described in a particularly vivid image, of the gift of food (grain) returned to those who themselves give: “a good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap.” This agrarian abundance is a far cry from gold and silver, but the reminder of daily bread is fitting as Jesus speaks to a crowd whose own prosperity was only as secure as the yield of the last harvest, or the whims of rulers and landlords. God’s care and reward are what we need, and given unstintingly.

If the true order of love defies appropriation for chauvinistic politics, nevertheless there is no easy escape from Jesus’ call for the earnest liberal or appalled progressive either. The fact that it is presently so easy to see the lack of moral substance in some others’ public actions is a spiritual danger. Jesus does not call us (just) to assess or decry the policies of others, but to act as though the God of the beatitudes were real. He thus tells those who listen not to judge, which should cause the earnest critic of the evils being done at present to pause for breath; God’s mercy is not constrained by our own views of how much others may need it, nor by whether they deserve it.

Loving those who are good, and those we know, as well as those are the victims of evil or exclusion, is necessary, but we cannot stop there. One of the commands Jesus gives is to “pray for those who abuse you.” If we are to love our enemies, we must stand with the poorest and most marginalized, but we cannot leave the powerful abusers of the present time off our prayer lists either. And after all, they need it.

Summa Theologiae 2.2.31: “puta si sit in extrema necessitate, quam etiam patri non tantam necessitatem patienti.”

It is easier to love a powerless enemy, than one who is stepping on your neck! It begs the question, "What good will it do?" Like so many of the prophecies of the mighty being cast down or of the poor lifted up, it can seem like nothing changes today, in the here and now. This means that we are compelled to ask if our faith is transactional only, or if there is more to this "godliness" than we can imagine or actually wish to embrace! It's not like we weren't warned: the rain falls on the just and the unjust.

Thank you for this reminder of the challenge of our trust in God!

As always, Andrew, I am very grateful for your commentary. I am especially grateful this week that you have so concisely and carefully rebutted the VPOTUS concerning his "ordo amoris". And the lectionary might even expand on your key insights here with the portion from Genesis of the Joseph cycle: sometimes our "enemies" or the ones who "abuse" us are in fact members of our own family--a reminder, perhaps, that who we consider to be "lovable" is entirely beside the point. Love (only love?) carries the power to transform...