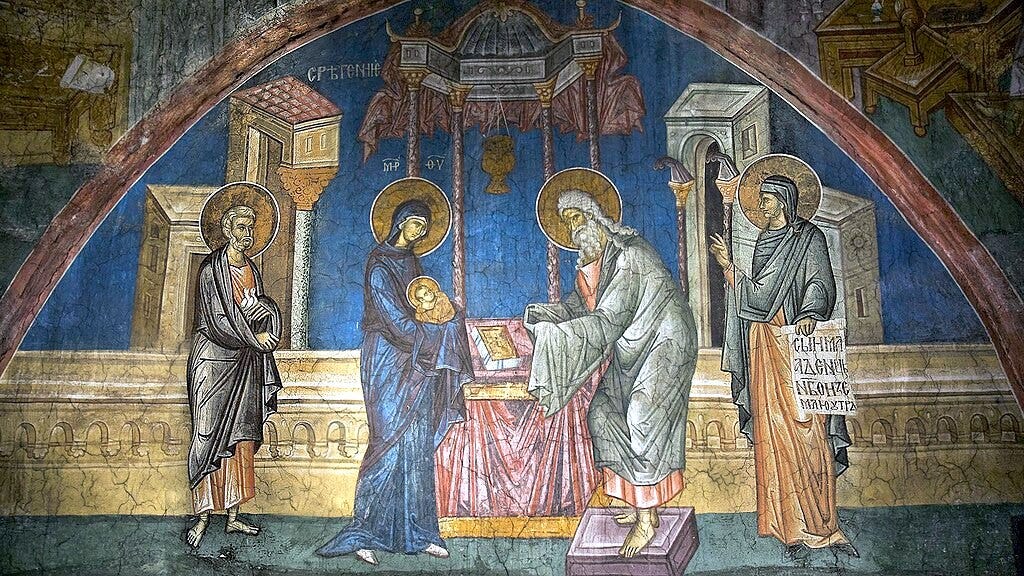

This story concerns events undertaken by Jewish parents after the birth of a male child, commemorated in Jesus’ case forty days after Christmas on this Feast of the Presentation. There are actually two different rituals combined in this passage, neither of them quite a “presentation,” although Luke’s treatment of the story makes that an apt title.

The first is that of “purification,” from which the Christian feast often took its name until modern times.1 Leviticus 12 specifies forty days of liminality after childbirth, “in purification.”2 Christian eye-rolling at this concern for purity needs to be checked. Despite the weight our own tradition has given it, to be “unclean” or to need “purification” did not mean being stigmatized or marginalized, but was a Jewish ritual response to events that were a necessary and often positive part of life. Purification was required after sex, childbirth, menstruation, or after necessary acts of kindness and charity involving the sick or the deceased. The post-partum mother was not a pariah or sinner, but someone whose return from the border between life and death—bearing in mind pre-industrial infant and maternal health risks—was being recognized.

Purification meant a visit to the Temple and a prescribed pair of sacrifices (Lev 12), an ʿōlâ—a whole burnt offering—and a ḥaṭṭā't, traditionally but misleadingly translated “sin offering.” The first of these (see Lev 1) involved the destruction of the victim by fire and hence and its transfer entirely to the divine realm, but its purpose was not very specific, and might be understood as offered as a sign of thanks or praise. The second (Lev 4) is for not for “sin” despite traditional renderings, but for purification; not where someone has acted badly but, as in this case, after some anomalous or difficult experience, to normalize or restore order.3 There is no implication of fault, any more than of exclusion. That the two offerings are here made in the form of doves or pigeons implies relative poverty on the family’s part (see Lev 12:8).

Quite separate but coinciding is the requirement for the “redemption” of any first-born child (v. 23). Here Luke has quoted from the Mosaic Law (Exod 13) which states that all the first-born —animal as well as human—belong to the Lord, and also that they be sacrificed (if animals), or in the case of children “redeemed” by the sacrifice of a lamb. Scholars tend to see a connection between this legislation and child sacrifice. There are famous polemics against such practices in scripture, but there are also some hints that child sacrifice may have taken place in Israel, and not just in service of foreign deities.4 Nevertheless, in Jewish experience as known in Jesus’ time the redemption process was symbolic and economic in form, made via a payment of five shekels (Num 18).

Luke ‘s account offers a curious lack of precision about what redemption actually means here, though. While he quotes the Exodus text that affirms how the first-born belong to God, the payment of the shekels to the priests is not mentioned (see below however on v.27), and despite Luke’s citation of the redemption command, most commentators think this expected payment did not require attendance at the Temple anyway.

Yet this fuzziness may be important. It makes little sense after all (in Luke’s perspective, or ours) for Mary and Joseph to “redeem” Jesus for themselves, for this child will always belong to God. We have already heard this point made earlier this year, given the out-of-order sequence the lectionary gives us, where the visit made by the twelve-year old Jesus to Jerusalem and the Temple—which follows straight on from this one— has been presented as his engagement in the “family business” (v.49).

The redemption of the first-born is alluded to again in v. 27 when Jesus’ parents come “to do what was customary under the Law.” This oblique turn of phrase allows us to note Mary and Joseph’s piety, and Jesus’ own position as observant of religion, but again makes no reference to a payment. The focus of the story lies on Jesus’ arrival, or presentation by his parents, in a place he seems already to belong, and which will continue in some sense to be his. And it is the two prophetic figures Simeon and Anna, rather than the priests who were recipients of the redemption price, who welcome Jesus to his true home in the Temple.

Simeon is a “righteous” and “pious” man but holds no office, although the repeated references to the Spirit (vv. 25, 26, 27) help us recognize his actions and words as prophetic. Simeon’s hymn of thanks and joy, known from the Evening Prayer of many traditions (“Nunc dimittis”), adds to the set of hymns Luke has already presented in the infancy narrative. The tone of the song suggests eager longing and its fulfillment, celebration that the appearance of Jesus is God’s work, and that the child himself is the Messiah (v. 26).

As in the later parts of Isaiah and elsewhere in prophetic literature, this new light is not merely for Israel, but for the nations; Jesus’ presence here in the holy city is a sign of universal salvation. Yet the epilogue to Simeon’s praise is more ambiguous; his word to Mary, that Jesus will be opposed and that a sword would pierce her own soul, is ominous. This message to her is personal, but representative; she will experience something that Israel itself will also undergo. The salvation Jesus brings will be rejected by some and embraced by others, ironically because of its universal scope.

Luke often presents male-female (and other) pairs, and Anna is a foil or complement to Simeon, but given a more formal designation than he as prophet (v.36) and a more impressive ascetic pedigree—she seems to have made the Temple precinct her home which implies a sort of affinity with Jesus, who has come home.

While Anna’s own verbal response to the child’s presentation is not directly included in the narrative (to general regret, whatever the reason), we should not pass by what is reported about it. She began “to speak about the child to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem” (v. 38). Here at last we find the “redemption” language that might have been expected sooner in relation this first-born child. It turns out however that he is not so much redeemed as redeemer, central to the work that God does to save all people rather than requiring ritual processes to regularize him.

The promise that Israel and Jerusalem themselves will be redeemed is the heart of this story. Jesus has come to the Temple—where reconciliation, forgiveness, purification, celebration, and redemption were all centered in sacrifice. He offers no sacrifice of his own because his relationship with the God whose mysterious presence inhabits the Temple does not require any further exchange or process. This redeemer has come not so much to undergo redemption as to enable, to proclaim, to administer the gifts God offers all people through Jesus.

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer was the first of the Anglican Books to use our present terminology; 1549, 1552, and 1559 all called it the Purification of the BVM.

The doubled period for female children probably represents a compounding of the mother’s and daughter’s liminality as both child-bearing, in principle.

See Jacob Milgrom, Leviticus 1-16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible 3A. New York: Doubleday, 1991, pp.225-6.

See (e.g.) Exod 22 where no redemption process is specified, and Micah 6:6-7, etc.; and the discussion in Jon D. Levenson, The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1993.

Thank you. I appreciate your commentary.