The lectionary now moves across to John, and to the story of a woman anointing Jesus’ feet shortly before the events of the Passion. Luke does have a similar story (see below) but it is not related to Jesus’ last visit to Jerusalem. Anointings somewhat like this one are found across all the Gospels, but they vary to the extent that we cannot be quite clear whether we are meant to think of one, two, or more occasions where a woman anoints Jesus.

Mark (14:3-9; followed closely by Matthew 26:6-13) offers a story with a number of close parallels to this one: both take place at Bethany shortly before a Passover, Jesus is anointed with a perfume made from real nard valued at 300 denarii, this gives rise to anger by disciple(s), Jesus defends the woman’s action, and then interprets it in connection with his burial. Unsurprisingly then, most commentators see John’s story as an adaptation of Mark’s. Yet there are also details here reminiscent of a different anointing story in Luke (7:36-50). In Luke and John a woman covers Jesus’ feet with an expensive perfume and dries them with her hair, while in Mark’s story the woman anoints Jesus’ head. Yet the woman who anoints for Luke is notably a “sinner” (7:47) which is not the case in John, or Mark.

The story in Mark ends with Jesus’ statement that “wherever the gospel is preached in the whole world, what she has done will be told in memory of her” (Mark 14:9). Yet, as Elisabeth Schüssler-Fiorenza pointedly notes, the fact the woman is not named makes Jesus’ pronouncement ironic at best.1 This quasi-remembrance has been further compromised as the different anointing stories became conflated in popular memory, including through attempts to connect them to the somewhat confusing array of “Marys” in the Gospels. By the time of Gregory the Great (c. 600) the sinful woman of Luke’s version is taken to be Mary Magdalene, who is by extension supposedly this Mary too.2 Many of us will have some version of this confusion at work in our minds, and so here we really are invited to read and to remember.

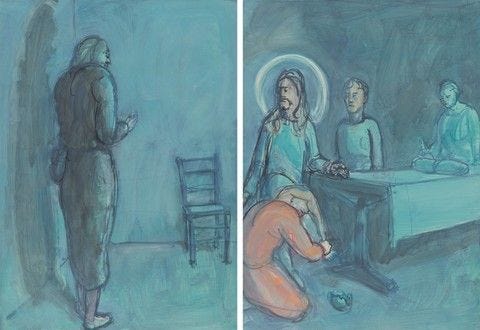

John’s version of the story is a counterpoint to this anonymity, as well as to the conflation of Marys, and so an act of specific remembrance. Not only is the deed important, its agent now is too. Mary is the sister of Martha, and of Lazarus whose dramatic rising has just been narrated (John 11:1-44). Mary and her family have a remarkable prominence in Gospel tradition, another connection with Luke (10:38-42). They have all been main characters in the previous chapter, and the link underlines Lazarus’ role as a precursor to Jesus in his death and resurrection too, and of the woman as witnesses. It also keeps the opposition to Jesus, that in this Gospel is focussed on Lazarus’ raising, as part of the atmosphere in this meal scene. The action that is performed here is not an abstract symbol; it happens to Jesus embedded in the intimacy John has sketched between Jesus and this family, and the growing hostility directed at him.

Anointing in the ancient Mediterranean world was not in itself unusual, but was part of what we might think of as grooming, hygiene, or cosmetics. Oil-based perfumes were the norm and used daily, at least by those whose means and lifestyles made that possible. So in the Sermon on the Mount Jesus urges followers who are fasting to “anoint your head and wash your face” (Matt 6:17), indicating nothing unusual was taking place outwardly. Sometimes an anointing is just an anointing.

Of course anointing was also used in ritual settings, as part of the initiation of those holding high office. In ancient Israel we hear of prophets, kings, and priests being anointed, and from this arises the idea of God’s chosen as “anointed one”—Messiah, or in Greek “Christ”—carrying some of the weight of all those other offices.

In this instance—in all the relevant stories, in fact—anointing Jesus starts not as an initiation or other specific ritual, but as a service that might quite normally be offered to guests at a banquet. Luke’s story makes that clearest, when Jesus notes how that woman’s acts—including anointing his feet— contrasted with an apparent lack of the niceties that might have been offered by the host, and lists anointing (of the head) among these (7:46).

Here however (and in Luke), it is Jesus’ feet that are anointed. This should probably be understood first and foremost as a more elaborate version of the typical foot-washing offered to guests (cf. John 13); to follow any form of washing with perfume was not in itself remarkable. Some commentators are also confused by wiping the perfume off, but wiping or scraping was also entirely normal; the scent persisted after the excess was removed. More remarkable is the use of her hair (cf. Luke 7:38), which is an unusual and deeply intimate act. While a feature in common with the Lukan story, here it has no connotation of penitence, but merely of a complete self-offering and devotion, underlining the point made by the expensive ointment.

It is less obvious though to take this as a sort of initiation to an office, for which Mark’s version, where Jesus’ head is anointed, seems more apt. So Jesus’ own commentary—a version of which is found in both Mark and John—suggests more that this act looks ahead to Jesus’ burial (v.7). There is also a contrast with the Lazarus story hinted at here; Martha had objected that there would be a stench after her brother had been dead four days (11:39); now, the house is filled with fragrance (v. 3). So the idea of an anticipatory anointing for burial is clear.

Yet we should not rule other connections out too quickly, in addition rather than as alternatives. Mary’s gift is one of massive value, and Judas’ wry comment that it could have been used to mount a welfare program evokes the work of great public figures who dispersed largesse on this scale. Judas’ objection and Jesus’ response always give pause for thought, but any twinge of concern about Jesus’ statement should be set against our present reality, where he is vindicated: poverty is as real as ever. Jesus does not brush off the issue, but notes that opportunities to act effectively to alleviate suffering will not end at that point. If we still have qualms, the assertion of Mary’s memory and identity are crucial here and often it seems overlooked. This was her gift for him, not his discretionary account; and it is her choice that determines how the valuable gift will be used, not Jesus’ or Judas’.

John’s timing of the event adds to the possibility that Mary’s action does also mark him, not merely as the one whose death and rising will echo Lazarus in death, but as a royal figure. Some will object that the anointing of the feet is less apt for a royal sign, but this I think is to reduce the varied symbolic potential of Mary’s act, as well as to miss the narrative force of John’s placement of the story. Mark’s anointing story takes place after the entrance into Jerusalem, but ours takes place immediately before the triumphal entrance, as a moment of preparation for it. C. K. Barrett thus suggests it can additionally be read as making a statement about Jesus’ royal identity.3

Of course this does not look like an enthronement ritual, but neither does Jesus’ imminent entry into Jerusalem on a donkey look (quite) like a royal triumph. In fact John often plays with expectations and pushes paradoxes forward for our consideration. It would not suit John’s picture of Jesus to suggest he is anointed as king at this point; he has always been king, but is also always a fit recipient of royal honors, which is what we are reading here. In the chapters to come, the failure of a whole set of people to recognize his kingship, and to mock it, will be a central theme.

What Pilate and the others will fail to see, Mary sees, and acts on. Remembering her choices is thus also to acknowledge Jesus as she did. Her act of devotion reveals something of Jesus’ identity, but also comes with the implied call to act on his observation that we inherit a sense of responsibility for the poor, those whose needs are met in the kingdom of God. Unlike earthly kingdoms, Jesus’ reign is not the realm of violence and force, but of love and self-offering. Mary in making this gift to Jesus also hints at what he himself will offer with and in his body, and what we are invited to give in his service.

In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983, xiii.

Barrett, The Gospel According to St. John; an Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text. London: SPCK, 341

Judas casts the choice between charity toward the poor and gifts of adoration are incompatible. John tells us his motivation for putting forth this dichotomy is selfish, but the thought persists in some religious circles to this day. I see Mary as offering us a glimpse of God's realm, where generous charity and extravagant adoration are both not just possible, but also inescapable; they are, simply, the way things are.