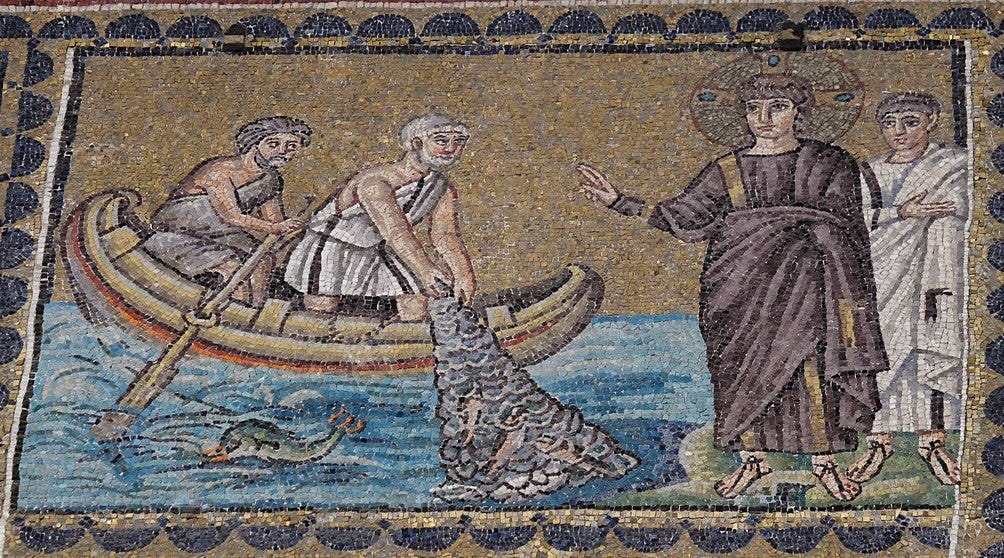

There is no single parallel to this story outside Luke, but there are at least two stories in other Gospels that are closely related. Luke is re-using Mark’s account of the call of the disciples (1:16-20) but places it later in the narrative, and focuses on Simon (“Peter” only comes later), as well as weaving in a story about fish not known elsewhere in the Synoptic tradition, yet reminiscent of a resurrection appearance in the Gospel of John (21:1-14). Questions of history here are therefore not easy, but not the main point; Luke’s “orderly account” (1:1) is his attempt to make theological as much as historical sense of the story of Jesus.

This episode involves an event of miraculous provision worth comparing to the Cana story (John 2) and the feeding of five (and/or four) thousand (Luke 9 etc.). As we have noted in discussing those cases elsewhere, the extraordinary provision of food hits differently when we consider ancient food insecurity as a backdrop. This is a little different though, in that while feasting and festivity for those present is implied in the other cases, here the miraculous haul is not for the onlookers—we may be supposed to think of the crowd as gone as soon as Jesus finishes speaking anyway—and so consumption plays no part in the story.

The path from the lake to the market or table is also a bit different than that from the farm for the grapes and grains; fishers are more like hunters, although their labor is also a necessary part of the provision of food. And here the producers themselves are the focus, where in other cases it was consumers. So while the miraculous catch is certainly food for someone, the fish are here more as a commodity than as a comestible, an unexpected source of wealth and support for this small co-op of fishing partners.

While the ancient reader will have got to this point less laboriously, we are all taken rather quickly to something (or things) else that the catch signifies than a good night for the fishers. There may already have been a clue in the way Jesus enlisted Simon’s help as he faced the challenge of teaching the “crowd” (5:1—or even “crowds,” 5:3). Jesus has been ministering alone through the previous two chapters. Simon has only been mentioned prior to this as householder whose mother-in-law was cured by Jesus (4:38-9), and is not yet a follower or helper, until Jesus makes him one here. So too, the assistance needed from the fishing partners (5:7) implies a communal task and not just an individual one. This isn’t just about Simon, nor just about fish, but about the expansion of Jesus’ ministry.

Simon’s self-identification as “a sinful man” isn’t really an invitation to biographical speculation, although it does resonate with Jesus’ coming association with other “sinners” that Luke will emphasize (see 5:32, 15:-12). Here it has more to do with the acknowledged unworthiness of anyone called by God to divine service, a recurrent biblical theme. The reading from Isaiah that accompanies this is one obvious case, with the prophet’s complaint that his unclean lips cannot be the medium for God’s word (Is 6:5). Moses’ attempt to refuse the divine calling he is given in Exodus (3:11) is also in the background here.

This more than a sort of literary trope. These stories present the awe involved in encounter with the divine, a necessary sense of inadequacy to any task that comes from the source of all, or even to being in the same place as God. The first thing we are meant to realize, then, is that Simon is indeed having an experience like those of Moses and Isaiah, but before the man Jesus rather than at a burning bush or during a vision of the heavenly realm. Jesus’ lakeside teaching and all this fish turns out to have been a theophany; the “word of God” (5:1) shared was not merely about propositions or parables, but his own presence there among them.

The appearance of God among us in such stories is never primarily an answer to a quest for spiritual growth or religious experience. It is, as here, about a call or a mission that must be undertaken. The nature of this call is summed up in the curious terms Jesus uses to interpret the fish story: “Do not be afraid; from now on you will be catching people” (5:10b).

More than one reader in the past has winced at the inadequacy of the metaphor of fishing to the practice of making disciples. And of course many “evangelistic” efforts have treated potential converts with all the care and grace that fishers offer their catch. While Luke initially takes the phrase from the simpler version of the call story in Mark (1:17), our translation does not indicate how Luke seems to have noted the problem. Instead of “I will make you fishers for people,” like Mark, here we read “you will be catching people alive” (ἀνθρώπους ἔσῃ ζωγρῶν). Every metaphor has its limits, but this one gets a bit more life via this shift: Jesus has indeed been fishing, and not just for what turned up in the nets.

Here the fish and food element is worth remembering again. The fishers have worked all night and face not the frustration of the sporting angler but the hunger of the fruitless quest for food. Jesus, the story tells us, has food in abundance, and the means to obtain is not merely about his power, but about his call to work and serve with him.

A number of images proceed from this story into the tradition; fish here, and in the miraculous feedings, evoke Jesus’ power as well as care, and so too the image of the boat will be important. While I doubt we can say the ship or boat (or fish) has already become a symbol of the Church by the time Luke writes, here it functions as the means for the mission to take place, as well as the place where Jesus teaches, and where those whom he calls to share in the work gather and provide for God’s people.

The most foreign aspect of this for modern readers may not however be catching challenging amounts of fish in nets from wooden boats on the advice of carpenters, but the challenge to our assumptions about divine encounter. Simon here shares in the biblical tradition that God appears to and calls not the worthy, the earnest, and the holy, but sinners. This sometimes has to be understood as a message of inclusion of the other, and of subversion of human forms of oppression; it can also become an excuse for not facing our own need to be called from that state of distance from God we call sin.1

This story refuses such a choice between self and other. The call to bring others alive into the net cannot be undertaken with integrity unless the fishers know that they too have needed, and still need, to become part of this community that receives God’s unlikely call and gift.

Barbara Reid OP and Shelly Matthews point out that Luke does not offer a picture that supports the popular idea of Jesus associating with “outcasts”; see Wisdom Commentary: Luke 1-9. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2021, 166 n.7

The fishers caught in God's net.... perhaps this is a case of "who could understand the call to catch people better than those who themselves fish, those who now are themselves caught?"

As ever, thank you for your insights!

Has no one ever heard of the word "hooked"? Yes, it hurts, and yes it saves.