Now, already one week into the liturgical year, we actually read the beginning of Mark’s1 Gospel.

In a way that will become familiar, we do not find ourselves pausing to savor the style or structure of this work; the content is too bare, too urgent, to warrant stopping. To begin the Gospel is to get underway, and keep going.

This Gospel will be short; it does not provide enough material to spread across the whole year, so later we will read more of John than in other years. It also does not conform to the expectations we might get from each of the others (despite their differences), of the ministry and teaching of Jesus as an extended or stable career, that ends with the dramatic events of his passion. Rather Mark is all about the end, and getting there as soon as can reasonably be done. As one famous description puts it, this Gospel will be “a passion narrative with an extended introduction.”

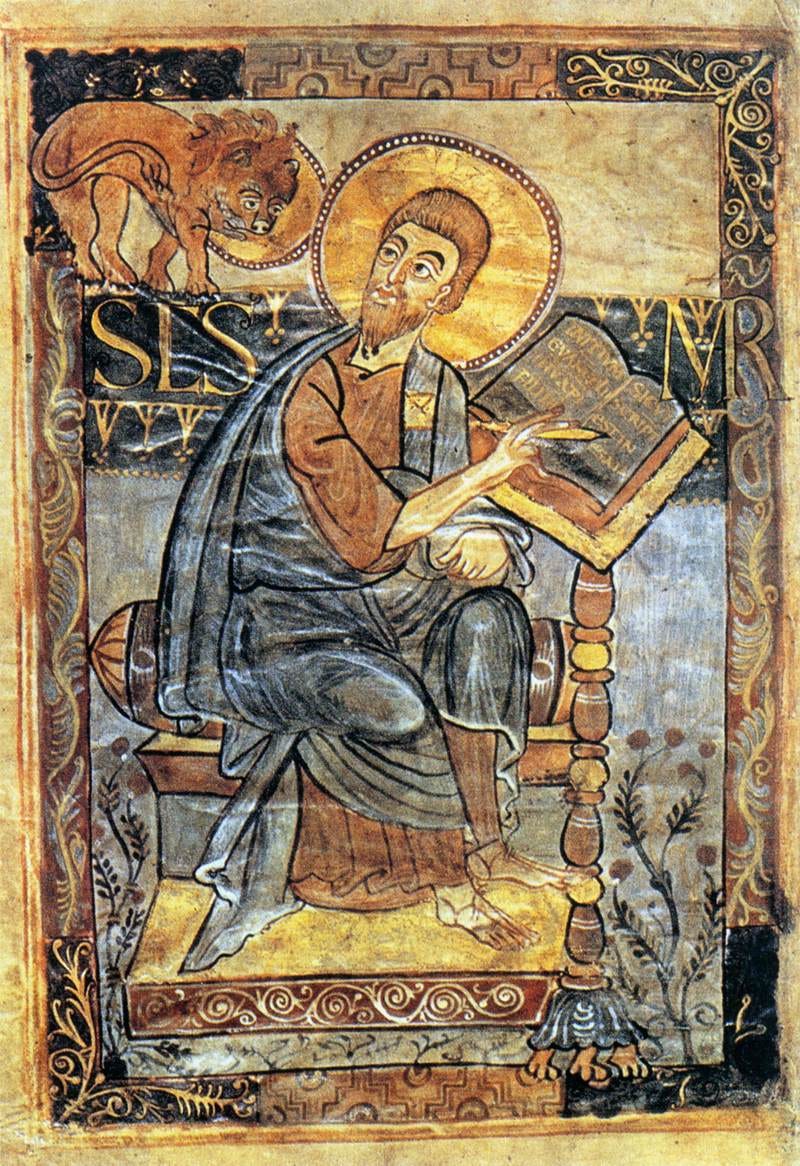

Mark is generally held to be the first Gospel written, which is one reason for its unadorned and single-minded nature. Matthew’s and Luke’s Gospels are effectively new editions of Mark, that borrow most of its content and add generously from other sources; Mark is by implication a more sparse and less developed product.

While we might be justified in attributing the sense of urgency that pervades Mark to the author’s theological purpose or literary style, there is another reason suggested in the very title, if we can call it that, with which Mark begins:

“The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

When Mark opens with those words, the work is not referring to itself. No-one had previously thought to apply the term “gospel” (euaggelion) to a piece of writing, or to a genre of biographical treatment of Jesus.

The term gospel was however already in Christian use, in that other familiar sense found considerably earlier in the letters of Paul. In Romans chapter 1 alone, Paul uses “gospel” four times to refer to the content of the message about Jesus: “the gospel of God,” “the gospel of his Son,” “preach the gospel,” and “the gospel of Christ” all appear within a few verses. And clearly Paul does not mean biography, but the news of salvation.

“Gospel” or euaggelion means “good news” but had a somewhat more specific meaning even before Paul. Roman emperors would couch announcements about their benefactions as a kind of euaggelion, in ways familiar today when a “major announcement” of some kind is forthcoming in political or commercial realms. Paul, and presumably other early Christian teachers and leaders, thus presented God’s good news as this kind of proclamation, but from the real source of all authority, as something that would outshine the claims of Augustus and his successors about successful wars, finished roads, and new appointments. This would be an announcement really worth hearing.

Although some scholars emphasize Mark’s re-use of the term to describe his own writing, I suspect we do him a disservice by exaggerating his intention to innovate or pioneer a literary genre, or to label it. The idea that the term “gospel” could apply to works like this could only come later, when the ones we know (and others too, outside the canon of scripture) seemed to have becme a recognizable form of writing, and hence an alternative to the earlier Pauline sense, of the message itself. It took some time for Christians to accept the additional sense of gospel as a written work of which there could be more than one; only late in the second century do we find for the first time, in writings of St Irenaeus, an attempt to make sense of how four works of this name could relate to the one “gospel.”

We could go further however. NT scholar Matthew Larsen suggests that the nature of Mark’s work—including its abrupt beginning and end—might best be explained by considering it unfinished.2 Mark’s work is notes, rather than a polished or published work, that found its way into circulation more by accident than design. The “title” is then not really a title at all; we should read Mark’s use of the term more like Paul’s, even though the narrative that will follow has its own characteristics. Mark is not presenting biographical information per se, but noting the content of what Paul also thought of as “the gospel,” the reason that one might follow and believe in Jesus.

So “the beginning of the good news” here is more a heading than a title, a heading for the notes Mark has received or recorded about what Jesus did and taught, and especially what he underwent in the events of his passion and resurrection. “Gospel” is still what Paul meant by it, the message about Jesus.

And so this is the beginning. There is no nativity story here (whether Mark knew any is very doubtful), but we do nevertheless look far back in history for context. The prophet Isaiah actually starts the gospel, and in fact Isaiah’s and then John the Baptist’s words—both a sort of proclamation, euaggelion—of who and what was coming, are very much “announcements” that help make sense of Mark’s heading.

The whole of Mark is a narrative supporting the news that Paul proclaimed also, that Jesus Christ is the son of God. That fact, not this work, is the gospel. Here, then, begins Mark’s summary—urgent, dense, spare—of that good news.

I will use “Mark” here to refer to the unknown author and to the work.

Larsen, Matthew D. C. Gospels before the Book. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Thank you. An excellent introduction to my favorite NT book. I was reading an article by a scholar (whose name slips away at the moment) who translated The first line as "The origin of the announcement of Jesus the Christ." i.e. that the whole book is an explanation how we got to the proclamation of the crucified and resurrected Jesus.