The Gospel set for this second Sunday of Advent reads as though it is the beginning of Luke’s whole story, although there have been two chapters before this. We can imagine these resounding words (“In the fifteenth year…”) on the “opening crawl” of the movie version (think Star Wars—the real/first one). Scholars have speculated that an earlier edition of Luke may even have started here; clearer is that this is the point where Luke’s special material concerning the infancies of John and Jesus stops, and our author starts to rewrite the already-existing narrative of Mark. Whatever its compositional history, this passage amounts to a new start after the prologue concerning the mysterious origins of these two key figures.

Even in this short space, this is already the third time that Luke offers a “synchronism,” a chronological connection between the events of this story and those of wider history (see 1:5, 2:1). Luke places a unique emphasis on the events of Jesus’ coming as part of God’s action and presence in history, both in the history of Israel and in what lay beyond it in the Roman Empire. These verses also make the Gospel sound like one of the works of the prophets, which often begin with such a statement about the kings under whom the oracles were spoken (see Isaiah 1:1, Micah 1:1, etc).

Luke also uniquely emphasizes the geography of God’s work in Jesus. We are often being told in this Gospel of places as well as times, not just as matters of historical interest, but as markers of a narrative which proceeds both forward in time, and outward in space.

During this opening “drumroll” as Luke Johnson puts it, something almost opposite happens at first though: the evangelist moves inward, starting off with a view of the scene from a great distance by referring to the whole known world in the person of the Emperor, then zooming in to focus on Galilean and Judean authorities both civil and religious, making the Jerusalem Temple the implied focal point of the story—which has already been signaled in the infancy stories, and will indeed be the case through the Gospel. Yet this also implies that the story will eventually be about the world, and not just one corner of it (see Acts 26:26).

The account of John’s ministry (3:1-20 at least) is both its own era, a time between the events of the infancy stories and the coming of Jesus, and also the story very much of one place, the Jordan region. John had already been introduced in his own—or Zechariah’s and Elizabeth’s—very substantial infancy story, unique to Luke (1:5-25); so when he reappears now it is as “John the Son of Zechariah” (3:2). While the earlier stories are unique to Luke, the geography (and more) of this material drawn from Mark is presented a bit differently from Mark’s version (and I suspect from our usual imaginative pictures).

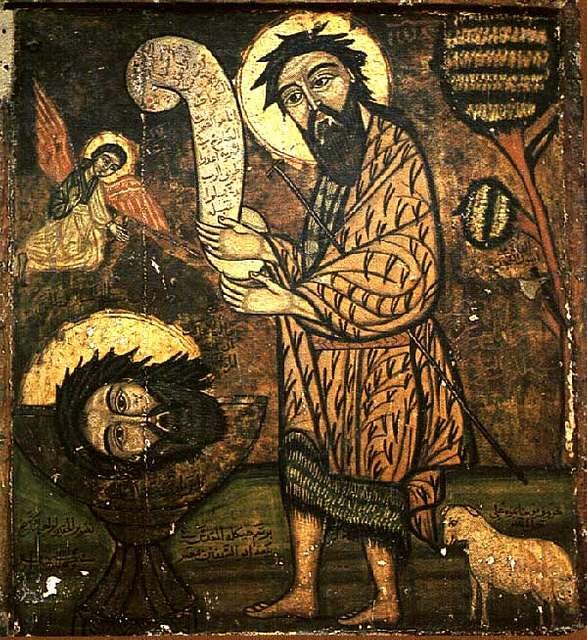

“The word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness” (v. 3b). Yet John isn’t the wild man of the desert here; there is no mention of camel’s hair clothing, leather belts, locusts, or wild honey. John doesn’t even stay in the wilderness once he has received the word, and in this version no-one comes out to the desert or the river to see him. Instead John is an itinerant, just as Jesus will be, and he himself “went into all the region around the Jordan.” This means the northern towns of the modern occupied West Bank, a term which refers, just as Luke’s language of “the Jordan” does, to the region and not just the river.

John’s activity here is preaching, first and foremost. We have no reason to think that the Jordan itself—still less one site on its banks— was the only place he baptized (although from the other accounts we can assume he did so there, wherever else).

All this makes John as the central figure both of a period of time and of God’s activity in a region. In this version, John’s arrest is reported straight after this, before the work of Jesus begins (3:19-20); so John’s small but significant era comes and goes entirely in this section, and we are not told that Jesus’ baptism (which comes after it) even involves John personally.

The familiar words from Isaiah that resound though Advent, both of a voice crying out in the wilderness and then the specific message it brings about places and how they change, take on a unique focus in Luke. Of course by the time the scripture is cited in the narrative, John is no longer in the wilderness, but this was where “the word of God” had come to him, so the text elucidates the message John had received, as well as functioning as a proof-text for his activity.

All the Gospels quote Isaiah 40:3 in relation to John’s ministry, but only Luke extends the familiar quotation to parts of vv. 4-5 that actually indicate what the voice is crying about and not just the fact of it:

Every valley shall be filled,

and every mountain and hill shall be made low,and the crooked shall be made straight,

and the rough ways made smooth;and all flesh shall see the salvation of God.

As John undertakes his tour of the towns of the Jordan region, he travels these roads and speaks to the inhabitants about a massive divinely-ordained civil works project. François Bovon imagines this as to “decorate and fix up the streets on which a prince or king must walk when entering a city.”1 The image is of preparation for a royal procession, preceding the appearance of a leader whose claims sit in obvious tension with those of Tiberius whose role has already been cited.

John here becomes the divine engineer, walking the roads of the Jordan that must be fixed for the arrival of the true King, and surveying what must be done, calling the inhabitants to the changes that must be undertaken inside and out. What these are can only be inferred, initially at least. Yet keen readers of Luke will recall, not many verses earlier, Mary’s exultant cry that God “has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty.” (1:52-3) This social leveling is at least part of what John’s message implies, and some of this will be clearer next week. Yet the core message is the coming of the one who will soon travel these roads, now become the way of “the Lord” whom we know to be Jesus himself; in him all flesh—not just those in one place—will see the salvation of God.

Bovon, Luke 1: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 1:1 - 9:50. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2002., 121-22.