The Present and Coming King

Sunday of the Passion (Palm Sunday) Year C 2025; Luke 19:28-40, 22:14-23:56

Τhe “Palms” Gospel and the Passion narrative, both read from Luke this coming Sunday, feature some of the most important and distinctive material in the whole Gospel. A considerable part of this distinctiveness concerns Jesus’ identity as King. Jesus is of course a king, but Luke is concerned that we not misread the events of the Passion. A recurrent theme here is Luke’s clarification that Jesus has not come to claim immediate political power as he enters Jerusalem, but to complete the “departure” (exodos) of which he had spoken to Moses and Elijah at the Transfiguration, the turning point of the Gospel, and towards which he has been moving ever since. The fulfilled reign of Jesus will be in the future.

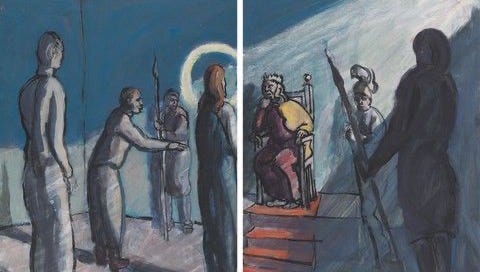

Despite the intimidating amount of material to be read, it is worth going back just before the Gospel for the Palms, to read Luke’s version of the Parable of the Talents (19:11-27) to understand Luke’s position. Mark and Matthew had placed this parable much earlier, in the midst of Jesus’ ministry, giving rise to the usual interpretation about being fruitful or conscientious with God’s gifts. Here however it is told to the disciples “because they supposed that the kingdom of God was to appear immediately” (19:11). And instead of being a wealthy property owner, the absentee who entrusts his servants with great wealth is in Luke a nobleman who is going away to receive royal power, and who will return transformed in status. This now becomes a sort of allegory of the Passion story, and what lies beyond it. Jesus’ “departure” is like the beginning of the parable, the nobleman’s leaving. Jesus’ royal power will however be unmistakeable when he returns—which is not yet.

All versions of the Palms story depict Jesus as king during the journey into Jerusalem, but Luke (19:38) lessens any sense that Jesus is now claiming a kingdom. Strikingly to this effect, this is not much of a “Palms” Gospel at all, being the only version that has no branches signifying a victory being waved. Luke does include the cloaks cast on the road that confirm the royal identity of the rider (cf. 2 Kgs 9:14), but Jesus’ arrival in the place often identified—especially in the infancy stories—in this Gospel as Jesus’ true home, and his Father’s dwelling, is not a conquest or accession but a homecoming.

During the Palms(!) scene there is an exchange between some Pharisees and Jesus; they want him to rebuke those identifying him as king. He demurs, saying the stones would cry out (19:40) to acclaim him. “Stones” language recurs through the section (20:17, 21:5-6). “Stones” though are not rocks, but the dressed building materials of the city; so this is an architectural image, not a geological one. It is Jerusalem itself, the very fabric of the place, that would cry out its praise of the king. This leads straight into Jesus’ weeping over the city (19:41) which echoes his lament as mother hen (13:34) but which we do not read. The same theme however is picked up during the Passion Gospel in the wrenching exchange with the women of Jerusalem, foreseeing the worse things to come (23:28-31). All these uniquely Lukan elements underscore Jesus’ love for the city of his Father’s house (cf. 2:49) which —in a passage not read in the lectionary—he will shortly reclaim when he clears it of the merchants after entering the city (19:46).

The Passion Gospel proper begins with the Last Supper, where Luke (only) has an initial cup before the meal, and then (in most manuscripts) a second one, parallel to the other versions. This may reflect a Passover ritual where, instead of the typical meal-cup sequence of the ancient banquet, there were successive courses repeating that pairing. The word over the first cup (22:18) again emphasizes the kingdom as a thing of the future: “I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes,” i.e., until the time he returns as king to defeat his enemies.

Luke places here the argument among the disciples about who is the greatest, which for Matthew and Mark takes place long before they arrive in Jerusalem. While there is no foot-washing story here, Luke anticipates John’s presentation of the Supper as the place where service is taught as the true nature of leadership. “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them” (v.25) but this is not how actual power works. Yet again, the timing of the kingdom comes up: “I confer on you, just as my Father has conferred on me, a kingdom, so that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and you will sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (22:29-20). The disciples—now schooled as to what real authority means—have, like Jesus, a kingdom conferred on them, but its fulfillment is future.

The trial of Jesus begins before the Sanhedrin, and focusses first on the question of his identity relative to Messianic expectation and as Son of God (22:66-71). When he comes before Pilate however, the issue changes somewhat to the more secular question of kingship (22:3). This is Pilate’s first question—are you the King of the Jews?— and Jesus allows “you say so” (23:3).

Only Luke then includes an episode before Herod (23:6-12). This other king of the Jews (of sorts) is the “fox” who is the opposite of Jesus’ own “hen” (13:32-24), a predatory ruler whose interest lies in his own self-aggrandizement rather than in his people’s welfare; he exemplifies that lesson just shared at the supper. Doubtless Herod would have spent plenty of time at his own golf club, if they’d been invented then. Herod is about entertainment not leadership; he seeks to have Jesus perform some sign, but Jesus is silent before him (in Matthew and Mark, Jesus’ silence is emphasized as part of his interaction with Pilate). In this version it is also Herod who mocks Jesus by dressing him in royal robes and sends him back. All this only serves to remind us who the real king is, and will be.

At the cross there are at least two things unique to Luke. First is Jesus’ call, “Father, forgive them…” It is found only in this Gospel, although somewhat unevenly attested in the manuscript tradition. I lean to thinking it may have been omitted by some scribes influenced by the notion of Jewish guilt in particular than to have been added later. Second, the exchange between Jesus and the other two crucified with him is uniquely elaborated, as one thief mocks him and the other defends him.

The plea of the “good thief” to be remembered when Jesus comes into his kingdom—that is, in that future when the kingdom is established— is consistent with Luke’s picture. He is, by the way, one of very few people in any Gospel who address Jesus by name.1

In common with the rest of the synoptic tradition, Jesus been identified as King by the inscription over the cross, which here is closely joined to the verbal mockery (shared with Matthew) of him on the cross, suggesting that as king he should save himself. The exchange with the thief does in fact have Jesus saving. His word to the thief now has a present dimension, the exercise of the royal authority already in his possession. The emphasis on “today” in this promise is striking given what we have seen of Luke’s persistent focus on a future kingdom. This future though can have present significance; those entrusted with the talents were given gifts in the present also. So the thief will experience “paradise”—a familiar image now, but less so in Luke’s time, which seems to evoke ancient pleasure gardens and perhaps even a renewed Eden, that garden of closeness to God before theft and disobedience intervened. However we reconcile the future and present elements of these promises, the one who has faith in Jesus will be remembered by him, but is with him already.

If the entry to Jerusalem was a royal homecoming, not an accession to the throne, so too the cross is a departure, not a coronation. Jesus is already king, but his kingdom will be fully established when he returns; the thief shows the faith Jesus had commended to the squabbling disciples when reminding them of hope for the coming of the kingdom. The cross now introduces this present age, what is experienced by Luke’s readers then as now. Those who believe wait for him, with expectation, trusting that even in Jesus’ apparent humiliation and destruction, the power of God to save and to serve has been shown.

See Bovon, Luke 3.311

Man! I have really enjoyed your commentary! For the last decade + i have celebrated Passover, it has added so much depth to the story of Easter etc. and I live the way you point out this tiny reference at the transfig and again here, answering this question “if Jesus has died…. Then why are we still all here suffering?!” Because the Exodus isn’t the end pf the story, just one super climactic portion! Literally so much to say in a tiny series of sermons…. I try to keep my short sermons to ONE point but it’s hard. Thanks for your thoughtful reflections, i’ve enjoyed them a lot!

Alas, it seems a long time to wait....