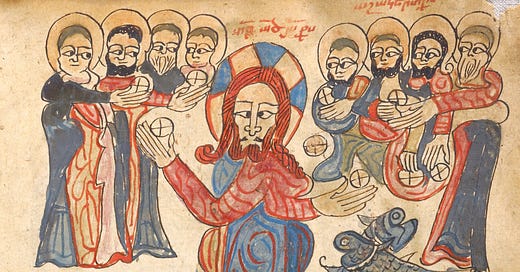

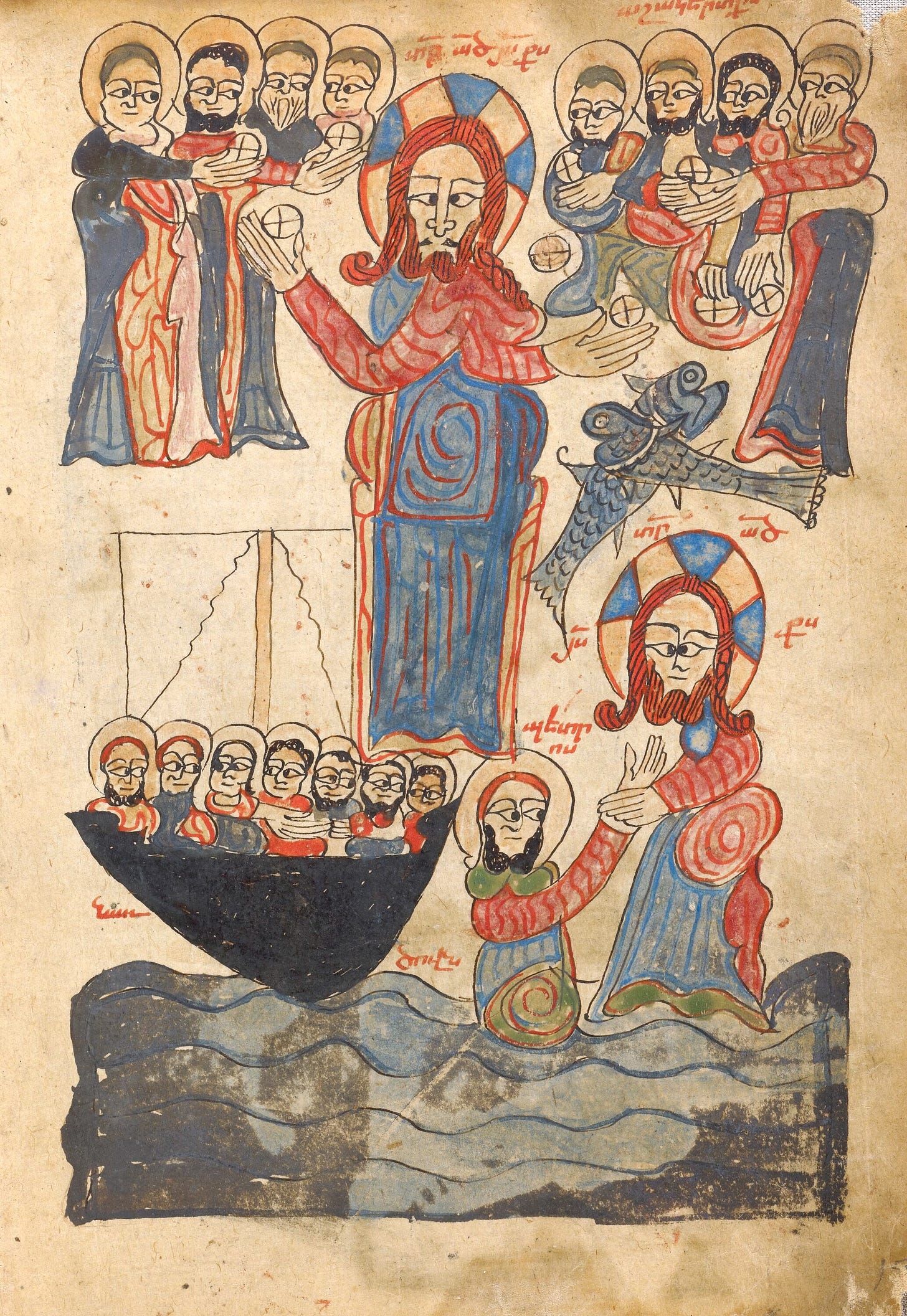

The miracle of the loaves is the only story common to all four Gospels, prior to the Passion Narrative itself.1 The commonality is greatest in Mark and John, where the story forms part of a sequence, with a lake crossing and Jesus walking through the storm following the feeding, before further interactions with the crowd. So this move by the lectionary from Mark to read that same set of stories in John’s Gospel for five weeks (!) is perhaps the only point at which to do so without losing touch with Mark’s narrative.

Despite the similar material, the perspective of John is distinctive. Christian interpreters have always understood the differences of sequence and content from the other three Gospels to mean that John has to be read in terms hinted at by the text itself: not just at face value, or as a mere record of events, but as an invitation to deeper reflection on the person of Jesus. Before 200, theologian Clement of Alexandria wrote:

But John, the last of all, seeing that what was corporeal was set forth in the Gospels, on the entreaty of his intimate friends, and inspired by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel (in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 6.14.7)

John’s narrative includes far fewer stories of Jesus performing miracles, but they often introduce extended reflection by Jesus and/or the evangelist about what has taken place. John calls them “works,” acts which witness to Jesus, and to the Father whose works he performs (5:36, 9:3, 10:32 etc.). These are also referred to as “signs”; while what they signify is specific to each event, as a group the “signs” are (as C. K. Barrett puts it) “special demonstrations of the character and power of God, and partial but effective realizations of his salvation.”2

The crowds come now because they had “seen the signs” (6:2). That does not mean those earlier signs or this one are understood, however. While this one sign will be elaborated in the following four weeks, there are some distinctive aspects of John’s version of the story itself. While the fact of the “sign” is testimony to God’s power to save, each one has something specific to say about that power. And here of course the sign centers on the reality of human need, hunger, and the capacity of Jesus to feed the crowd, but also (as the discourse of the coming weeks will show) to feed and serve humanity in all ways.

The Passover is near (6:4), a detail not mentioned in the Synoptic versions. This suggests a parallel with the gift of Manna to the Israelites during the Exodus from Egypt; that comparison will also be expanded on in the coming weeks. Not only can Jesus feed the hungry, but the sign reflects God’s care for the poor in their need, and for a people seeking freedom from oppression.

The dynamic between Jesus and the disciples around meeting the needs of the crowd is quite different here from the Synoptics. There, the disciples are the instigators, and come to seek Jesus’ intervention (primarily by wanting him to send the crowd away), after which he turns the problem back to them. Here in John, Jesus himself introduces the issue, and while he offers a kind of test for the disciples by asking Philip how the problem will be solved, and Andrew is highlighted in identifying the boy with the provisions, it ends up being Jesus himself who distributes the food, emphasizing his own role and power rather than that of the disciples.

Both Mark and John (not the other two, for whatever reason) mention the sum of 200 denarii as a potential cost for the exercise (which NRSV misleadingly tries to calculate in terms of some mythical average wage). Let’s just call it a lot of money, a sum beyond the means of a group of Galilean itinerants or peasants. This isn’t a catering and logistics problem, it’s an economic and social one. Jesus’ actions are those of a political leader who ensures the welfare of the people.

In the Synoptics the disciples seem to have the bread and fish themselves, but the emphasis on here the boy who has the supplies underlines the role of the people interacting with Jesus directly. The crowd are the rural poor whose resources are limited, who know hunger intimately, and are subject to the whims of unscrupulous landlords and imperial power alike. The economic dimension is also underlined by the very specific reference to barley as the material of the boy’s bread, also unique to John. Barley was cheaper, being easier to grow and less vulnerable to drought. It was also less desirable to refined tastes, the point being that simplicity and hunger are the backdrop, not taste. The barley reference also cements a parallel with the story in 2 Kings read by some as the first lesson, where the company of prophets fed by Elisha with barley bread was again not an elite group of jaded diners, but people conscious of dependence on God from day to day.

After the feeding, the people identify Jesus both as “the prophet” (14) and as king (15), both of which are true but inaccurate at the same time. As Wayne Meeks points out in his monograph on John’s characterization of Jesus, this combination of identities is reminiscent of another famous case of Johannine semi-accurate identification: Jesus acknowledges his kingship to Pilate, but defines it essentially as prophetic: “You say that I am a king. For this end I was born, and for this I came into the world, to bear witness to the truth” (18:37).3 Both these roles, of prophet and king, interpret each other and point to the relationship between Jesus and Moses made via the Passover reference and the manna parallel.

John makes very little of the following story of Jesus walking on water, which seems to have been inherited as part of an existing sequence with the feeding narrative, but in context it may form part of an answer to the crowd’s identification of Jesus. They understand that he is a new Moses and a true king, but they do not really understand how that is so, or what it means. As John has shown at other points (and made clear even in the prologue to the Gospel; cf. 1:17), Jesus is greater than Moses, even if the figure of Moses helps interpret the person of Jesus. His authority over the waves puts him in a different place.

The feeding story will serve as a reference for the long discourse in John 6 that will be anthologized in the coming weeks. Yet already John’s presentation of the sign has Jesus acting powerfully not just to demonstrate that power per se but to illustrate the nature of his messianic work. His salvation is more than economic and social, let alone dietary, but it begins with this act of addressing basic human need. What makes him king and prophet is not just power but compassion and leadership. The act of feeding will be elucidated in what follows, but cannot be forgotten. Like Moses he has come not just to feed his people but to set them free.

Setting aside the Temple incident which for the Synoptics is a prelude to the Passion, whereas for John it almost opens Jesus’ ministry (perhaps thereby making the whole more clearly a passion narrative in any case).

The Gospel According to St. John; an Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text. New York, Macmillan, 1956, 76.

Wayne A Meeks. The Prophet-King: Moses Traditions and the Johannine Christology. Brill, 1967, 1-2 and passim.